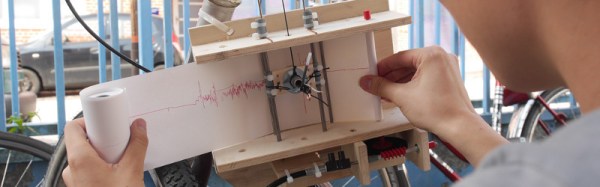

Riding the streets of the Netherlands on a bicycle is a silky-smooth experience compared to doing the same on those of Germany. So says [Kati Hyyppä], who made the move with her trusty Dutch bike. The experience led her to record the uneven cobblestones and broken asphalt of the German roads on a home-made seismograph, a paper chart recorder driven by the bike’s motion and recorded upon by a pen free to vibrate as it passed over any bumps.

The resulting instrument is a wooden frame with a ballpoint pen mounted in a sliding holder weighted with some washers and kept under some tension with elastic bands. The paper roll is driven from the motion of the bike by the drive from a mechanical speedometer feeding a set of FischerTechnik gears, and the whole unit is suspended from the crossbar.

You can see it in action in the video below the break, and if you would like to build one yourself she has put the project up on Instructables as well as posting the description linked above.