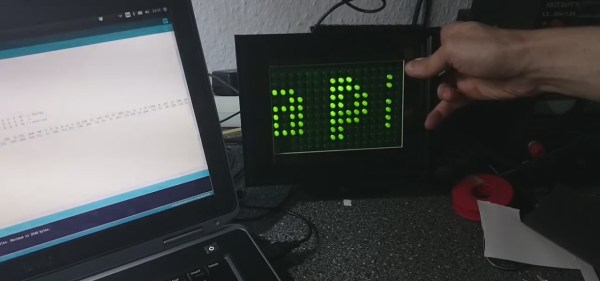

[Cupcakus]’s mini Apple IIe must surely be a contender for the smallest computer running an Apple II emulator. We’d mentioned it a few months ago in a Links post when it had been posted to a forum along with a few videos of it in action, but now popular YouTube channel, [Tested], has released a video wherein they not only show what’s inside, and interview [Cupcakus] about his trials and tribulations in making it, but also go through the steps of making one of their own. Also, at the time of writing the Links post, [Cupcakus] hadn’t yet announced his detailed GitHub page about it.

This mini Apple IIe runs on a C.H.I.P., a small $9 single board computer, and has a speaker and a TFT LCD display. Input is via a full-sized wireless keyboard. He doesn’t have joysticks working but that was an oversight and having realized how many games require joysticks, he has plans to add support for them. The case is 3D printed from models available on Thingiverse and links are on the GitHub page, along with all other details for making one yourself.

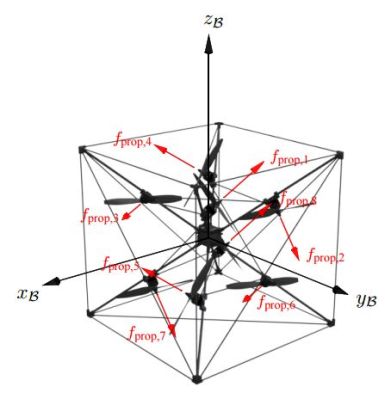

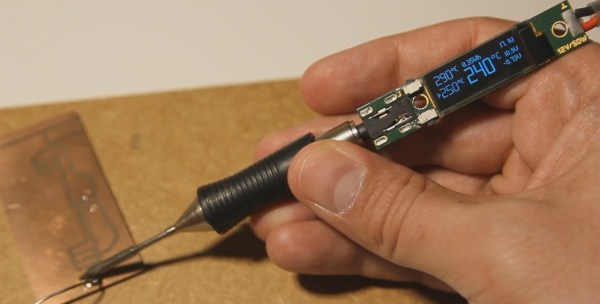

He did have to do some hacking. The video signal from the C.H.I.P. wasn’t available from the pin headers so he had to solder a wire directly to the board itself. The C.H.I.P. requires from 3.3 V to 5 V whereas the display wants 6 V to 12 V. To accommodate both he gets power from a 12 V drone battery and uses a 5 V buck converter for the C.H.I.P. And he had to modify the emulator to be legible on the low resolution of the display. The code for that is also available through the GitHub page.

While he uses the display as the screen for the Apple II emulator, it actually has two video inputs. So just in case he wants to show something on the display from another source, perhaps to watch a video, he’s made the second video input available using a socket in the back.

Want to see all the details for yourself? Check out [Tested]’s video below.