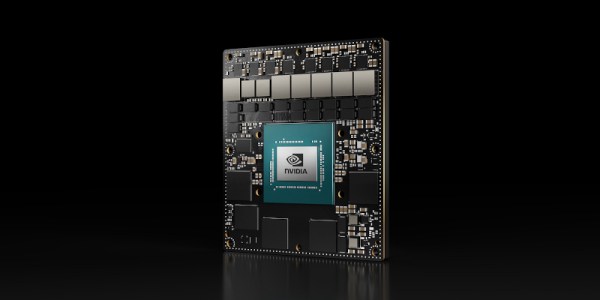

Back in March, NVIDIA introduced Jetson Orin, the next-generation of their ARM single-board computers intended for edge computing applications. The new platform promised to deliver “server-class AI performance” on a board small enough to install in a robot or IoT device, with even the lowest tier of Orin modules offering roughly double the performance of the previous Jetson Xavier modules. Unfortunately, there was a bit of a catch — at the time, Orin was only available in development kit form.

But today, NVIDIA has announced the immediate availability of the Jetson AGX Orin 32GB production module for $999 USD. This is essentially the mid-range offering of the Orin line, which makes releasing it first a logical enough choice. Users who need the top-end performance of the 64GB variant will have to wait until November, but there’s still no hard release date for the smaller NX Orin SO-DIMM modules.

That’s a bit of a letdown for folks like us, since the two SO-DIMM modules are probably the most appealing for hackers and makers. At $399 and $599, their pricing makes them far more palatable for the individual experimenter, while their smaller size and more familiar interface should make them easier to implement into DIY builds. While the Jetson Nano is still an unbeatable bargain for those looking to dip their toes into the CUDA waters, we could certainly see folks investing in the far more powerful NX Orin boards for more complex projects.

While the AGX Orin modules might be a bit steep for the average tinkerer, their availability is still something to be excited about. Thanks to the common JetPack SDK framework shared by the Jetson family of boards, applications developed for these higher-end modules will largely remain compatible across the whole product line. Sure, the cheaper and older Jetson boards will run them slower, but as far as machine learning and AI applications go, they’ll still run circles around something like the Raspberry Pi.