You asked for it, and now you’ve got it. It’s taken more than a decade of accumulated complaining, but this gigantic 555 timer IC has finally gathered enough psychokinetic energy to take corporeal form and demand fealty from the readers of Hackaday.

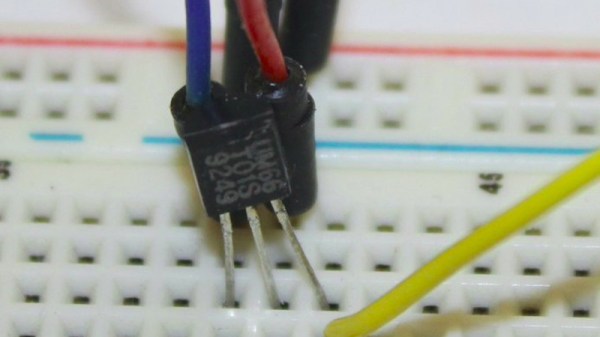

Or not. The less exciting explanation is that creator [Rudraksha Vegad] was looking for a way to combine his interests in discrete electronic components and woodworking. The result is an incredible build that’s more than just a conversation starter; this desktop-sized version of the iconic integrated timer circuit is fully functional. You can even hook it up to a breadboard, assuming you’ve got some alligator clips handy.

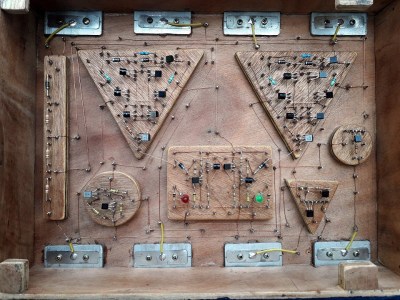

Lifting the lid on this wooden “chip” uncovers an intricate hand-wired array of discrete components that stand in for the microscopic goings on inside the real thing. He’s even gone through the trouble of recreating the symbols for the comparators and flip-flops that you’d see in a diagram of a 555 using wooden shapes to elevate their respective components. It might not fit the classical definition, but surely this must count as some form of circuit sculpture.

Lifting the lid on this wooden “chip” uncovers an intricate hand-wired array of discrete components that stand in for the microscopic goings on inside the real thing. He’s even gone through the trouble of recreating the symbols for the comparators and flip-flops that you’d see in a diagram of a 555 using wooden shapes to elevate their respective components. It might not fit the classical definition, but surely this must count as some form of circuit sculpture.

[Rudraksha] credits several other projects for not just inspiring him to create his own mega 555, but for helping him wrap his head around the internal workings of everyone’s favorite IC. Using components he salvaged from old hardware, he says the project ended up being very educational for him. These days, when most makers are more likely to reach for a microcontroller than a logic chip, spending some quality time with transistors and passives can be quite illuminating.

Continue reading “All Hail Your New Giant 555 Timer Overlord”

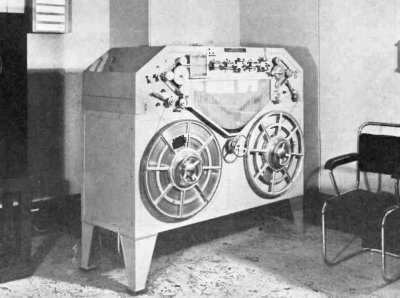

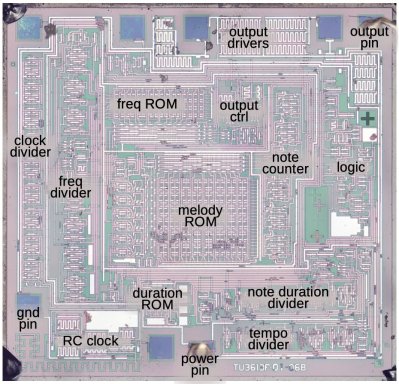

The surprise in this age of ubiquitous microcontrollers is that this is not a smart device; instead it’s a single-purpose logic chip whose purpose is to step through a small ROM containing note values and durations, driving a frequency generator to produce the notes themselves. The frequency generator isn’t the divider chain from the RC oscillator that we might expect, instead it’s a shift register arrangement which saves on the transistor count.

The surprise in this age of ubiquitous microcontrollers is that this is not a smart device; instead it’s a single-purpose logic chip whose purpose is to step through a small ROM containing note values and durations, driving a frequency generator to produce the notes themselves. The frequency generator isn’t the divider chain from the RC oscillator that we might expect, instead it’s a shift register arrangement which saves on the transistor count.