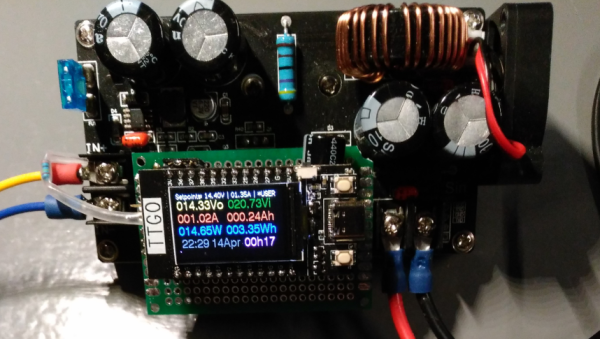

The Raspberry Pi has come a long way since its humble origins, adding faster processors and better interfaces with each new generation. Now, the Raspberry Pi 5 has a lovely new PCIe port right on board, and [Jeff Geerling] has gone right ahead and slammed in an NVMe SSD as a boot drive.

[Jeff] explains that to use an NVMe to boot, you first have to modify /boot/config.txt to enable PCIe and modify the Raspberry Pi’s boot order. Once the bootloader is appropriately configured, you can boot straight off an SSD with Raspberry Pi OS installed. To get the operating system on to an NVMe drive, he recommends cloning an existing boot volume from a microSD install.

One of the primary reasons you might want to do this is speed. NVMe drives are generally a significant cut above even the best microSD cards, both in speed and reliability. [Jeff] also notes that you can use an NVMe SSD through a PCIe switch on the Pi 5 if you so desire, but you can’t currently boot with this configuration.

It’s a great feature to have on the Pi 5, and it follows on from the earlier implementation on the Raspberry Pi Compute Module 4. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Booting The Raspberry Pi 5 With An NVMe SSD”