Vintage computer hardware can fail in a variety of fascinating ways, with [Bits und Bolts] dealing with an interesting failure mode, in the form of degraded MLCC capacitors on Voodoo 2 graphics cards. These little marvels of miniaturized surface-mount technology enable the placement of ceramic capacitors with very little space required, but as they degrade over time or due to physical damage, they can cause big issues in a circuit.

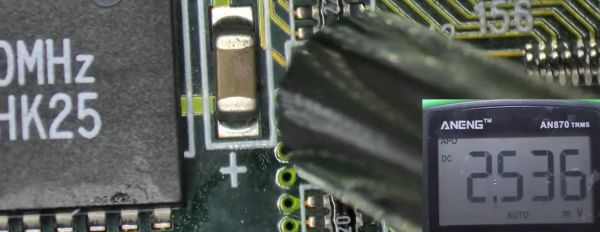

In the case of the two Voodoo 2 GPUs that [Bits und Bolts] was trying to fix, the clue that something was wrong was graphical glitches, which seemed to be related to something dragging down the 5V rail. Using the standard ‘inject voltage and see what gets hot’ method, he discovered a couple of dead MLCCs and replaced them. But something was still dragging the rail down. Unfortunately, whatever it was wasn’t enough to heat up the part in question, and no sane person wants to desolder hundreds or even thousands of MLCCs on a PCB and see whether it makes a difference.

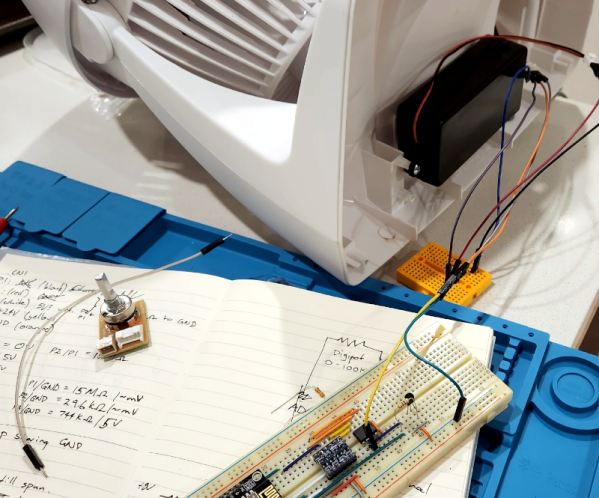

Ultimately, the pyroelectric effect was used to hunt down the culprit, saving countless hours of work. This is a property of certain naturally electrically polarized crystals, in which the material generates a voltage when heated or cooled. Materials like that used in MLCCs, for example.

Continue reading “Using The Pyroelectric Effect To Identify Broken MLCC Capacitors”