Aliens is the second film from the legendary science-fiction series about, well… aliens. Naturally, it featured some compelling future-tech — such as the M314 Motion Tracker. [RobSmithDev] wanted to recreate the device himself, using modern technology to replicate the functionality as closely as possible.

While a lot of cosmetic replicas exist in the world, [Rob] wanted to make the thing work for real. To that end, he grabbed the DreamHAT+ Radar HAT for the Raspberry Pi. It’s a short-range radar module, and thus is useless for equipping your own air force or building surface-to-air weaponry. However, it can detect motion in a range of a few meters or so, using its 60 GHz transmitter and three receivers all baked into the one chip.

[Rob] does a great job of explaining how the radar works, and how he integrated it into a viable handheld motion tracker that works very similarly to the one in the movie. It may not exactly keep you safe from alien predators, but it’s always fun to see a functional prop rather than one that just looks good.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen somebody try to replicate this particular prop, but the modern electronics used in this build definitely bring it to the next level.

Continue reading “Building A Functional Aliens Motion Tracker”

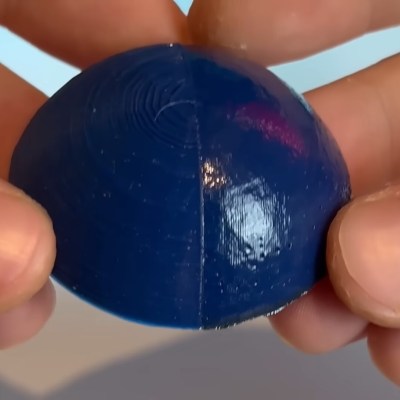

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.

The smoothing process begins at the end of a 3D print and uses non-planar printer movements to keep the laser at an ideal focusing distance. The results proved rather effective, giving a noticeably smoother and shiner quality than an unprocessed print. The smoothing works incredibly well on fine geometry which would be difficult or impossible to smooth out via traditional mechanical means. Some detail was lost with sharp corners getting rounded, but not nearly as much as [TenTech] feared.