Speech synthesis has been around since roughly the middle of the 20th century. Once upon a time, it took remarkably advanced hardware just to even choke out a few words. But as [atomic14] shows with this project, these days it only takes some open source software and 10-cent microcontroller

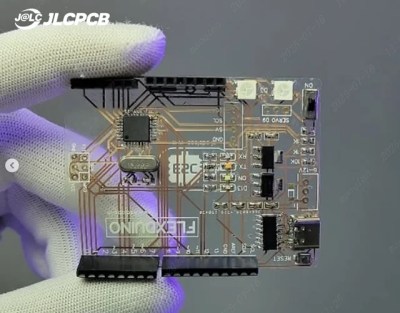

The speech synth is implemented on a CH32V003 microcontroller, known for its remarkably low unit cost when ordered in quantity. It’s a speedy little RISC-V chip running at 48 MHz, albeit with the limitation of just 16 KB of Flash and 2 KB of SRAM on board.

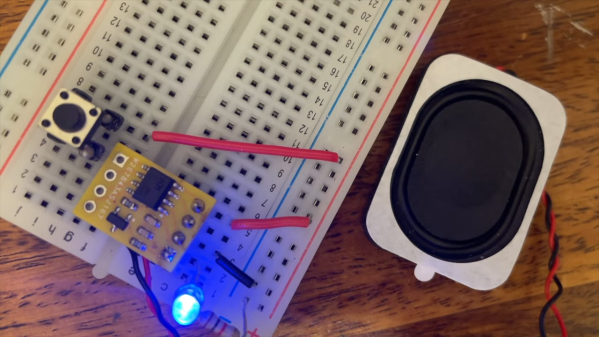

The microcontroller is hooked up to a speaker via a simple single-transistor circuit, which allows for audio output. [atomic14] first demonstrates this by having the chip play back six seconds of low quality audio with some nifty space-saving techniques to squeeze it into the limited flash available. Then, [atomic14] shows how he implemented the Talkie library on the chip, which is a softwarehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZvX95aXSdM implementation of Texas Instruments’ LPC speech synthesis architecture—which you probably know from the famous Speak & Spell toys. It’s got a ton of built in vocabulary out of the box, and you can even encode your own words with some freely available tools.

We’ve seen [atomic14] tinker with these chips before, too.

Continue reading “Speech Synthesis On A 10 Cent Microcontroller”