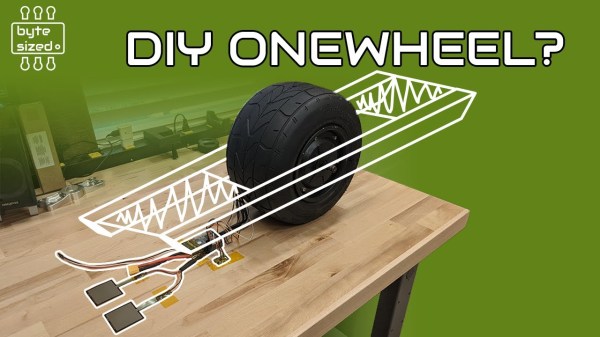

The story is one we’ve all lived: We see a piece of commercial technology and we want it, but the price tag makes us wonder if it isn’t made with gold pressed latinum. The object of [Zach]’s desire? A single wheel powered skateboard sold by a company called Onewheel. But as you can see in the video below the break, and his excellent website, Zach took the wallet-light but time-heavy approach and built his own prototype he calls the Openwheel.

Starting with a single powered wheel, [Zach] used aluminum, very large 3D printed pieces, and a really slick off the shelf controller package to control the Openwheel. Balance is handled by the controller, while a massive 48 V LiPo battery is fed through a beefy electronic speed controller that allows advanced features like regenerative braking.

We won’t spoil the results, but [Zach]’s Openwheel came out very nice, even exceeding some specifications of the commercial unit. You’ll want to watch his YouTube series about the build to get an idea of all the work that goes into such a device even as a prototype.

If tank track tread is more your jam, check out this tank track skateboard that we featured some time back!