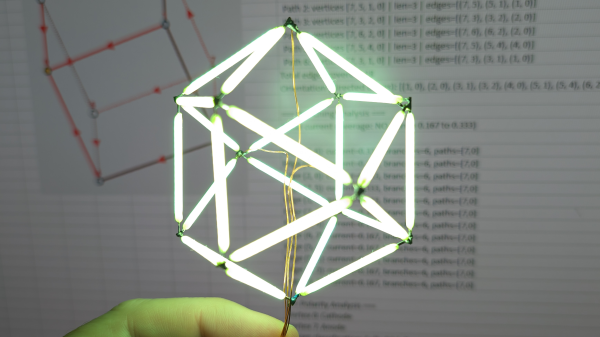

Like many of us, [Tim]’s seen online videos of circuit sculptures containing illuminated LED filaments. Unlike most of us, however, he went a step further by using graph theory to design glowing structures made entirely of filaments.

The problem isn’t as straightforward as it might first appear: all the segments need to be illuminated, there should be as few powered junctions as possible, and to allow a single power supply voltage, all paths between powered junctions should have the same length. Ideally, all filaments would carry the same amount of current, but even if they don’t, the difference in brightness isn’t always noticeable. [Tim] found three ways to power these structures: direct current between fixed points, current supplied between alternating points so as to take different paths through the structure, and alternating current supplied between two fixed points (essentially, a glowing full-bridge rectifier).

To find workable structures, [Tim] represented circuits as directed graphs, with each junction being a vertex and each filament a directed edge, then developed filter criteria to find graphs corresponding to working circuits. In the case of power supplied from fixed points, the problem turned out to be equivalent to the edge-geodesic cover problem. Graphs that solve this problem are bipartite, which provided an effective filter criterion. The solutions this method found often had uneven brightness, so he also screened for circuits that could be decomposed into a set of paths that visit each edge exactly once – ensuring that each filament would receive the same current. He also found a set of conditions to identify circuits using rectifier-type alternating current driving, which you can see on the webpage he created to visualize the different possible structures.

We’ve seen some artistic illuminated circuit art before, some using LED filaments. This project doesn’t take exactly the same approach, but if you’re interested in more about graph theory and route planning, check out this article.