With all the Nixie Clock projects out there, it is truly difficult to come up with something new and unique. Nevertheless, [TheJBW] managed to do so with his Ultimate Nixie Internet Alarm Clock (UNIAC) which definitely does not skimp on cool features.

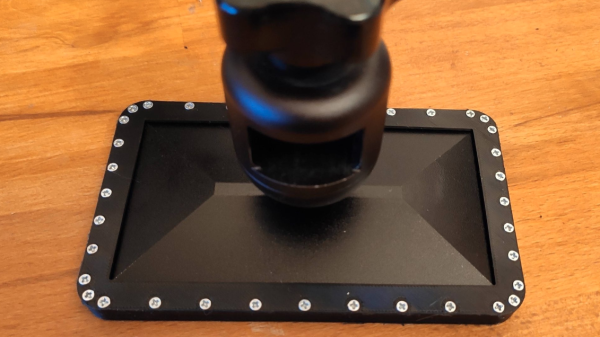

Although the device does tell time, it is actually a portable boombox that streams music from Spotify using a Raspberry Pi Zero running Mopidy. The housing made from smoked acrylic, together with the IN-12A Nixie Tubes, an IN-13 VU meter, and illuminated pushbuttons give this boombox kind of a 70s/90s mashup retro look. The acrylic housing is special since it consists of only two plates which were bent into shape, resulting in smooth edges in contrast to the often used finger or T-slot design.

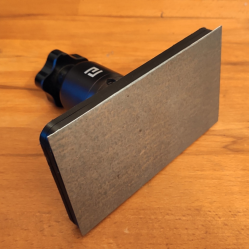

For his project [TheJBW] designed a general-purpose Nixie display that can not only show time and date but also the elapsed or remaining track time. He also came up with a Python generated artificial voice that reads you the current playlist. The only problem [TheJBW] has run into was when trying to design a suitable battery system for the device, as the high current draw during start-up can easily cause brownouts. Due to time constraints, he ended up with a MacGyver-style solution by taping a 12 V battery pack from Amazon to the back of the unit.

Among the large variety of Nixie projects we don’t think we have ever seen them in an audio player before except for some attempts of using them as an amplifier. However, it is known that IN-13 tubes make a great VU meter.