As flu season encroaches upon the northern hemisphere, doctor’s offices and walk-in clinics will be filled to capacity with phlegm-y people asking themselves that age-old question: is it the flu, or just a little cold? If only they all had smart thermometers at home that can tell the difference.

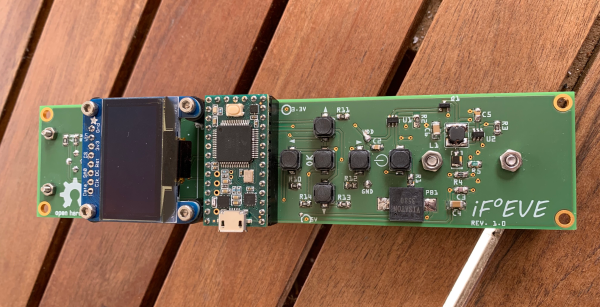

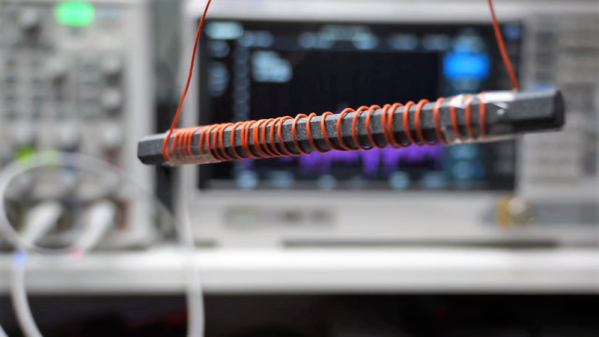

Typically, a fever under 101°F (38.5°C) in adults and 100.4°F (38°C) in children is considered low-grade, and thus is probably not the flu. But who can remember these things in times of suffering? [M. Bindhammer]’s iF°EVE is meant to be a lifesaving medical device that eliminates the guesswork. It takes readings via 3D printed ear probe mounted on the back, and then asks a series of yes/no questions like do you have chills, fatigue, cough, sore throat, etc. Then the Teensy 3.2 uses naive Bayes classification to give the probability of influenza vs. cold. The infrared thermometer [M.] chose has an accuracy of 0.02°C, so it should be a fairly reliable indicator.

Final determinations should of course be left up to a throat swab at the doctor’s office. But widespread use of this smart thermometer could be the first step toward fewer influenza deaths, and would probably boost the ratio of doctors to patients.