For anyone who’s seen a 1970’s era microcomputer like the Altair 8800 doing its thing, you’ll know the centerpiece of these behemoths is the array of LEDs and toggle switches used as input and output. Sure, computers today are exponentially more capable, but there’s something undeniably satisfying about developing software with pen, paper, and the patience to key it all in.

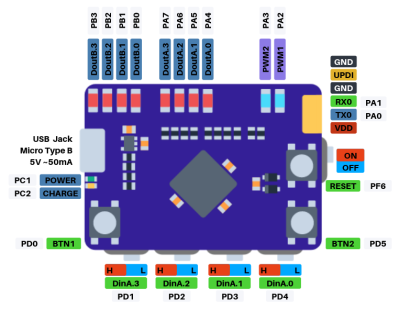

If you’d like to get a taste of old school visceral programming, but aren’t quite ready to invest in a 40 year old computer, then [GClown25] might have the answer for you. He’s developed a pocket sized “computer” he’s calling the BIT4 that can be programmed with just three tactile switches. In reality it’s an ATMega4809 running C code, but it does give you an idea of how the machines of yesteryear were programmed.

If you’d like to get a taste of old school visceral programming, but aren’t quite ready to invest in a 40 year old computer, then [GClown25] might have the answer for you. He’s developed a pocket sized “computer” he’s calling the BIT4 that can be programmed with just three tactile switches. In reality it’s an ATMega4809 running C code, but it does give you an idea of how the machines of yesteryear were programmed.

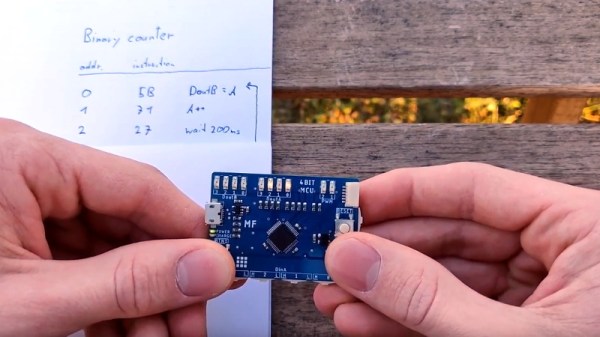

In the video after the break, [GClown25] demonstrates the BIT4 by entering in a simple binary counter program. With a hand-written copy of the program to use as a reference, he steps through the memory addresses and enters in the command and then the value he wishes to operate on. After a few seconds of frantic button pushing, he puts the BIT4 into run mode and you can see the output on the array of LEDs along the top edge of the PCB.

All of the hardware and software is open source for anyone who’s interested in building their own copy, or perhaps just wants to take a peak at how [GClown25] re-imagined the classic microcomputer experience with modern technology. Conceptually, this project reminds us of the Digirule2, but we’ve got to admit the fact this version isn’t a foot long is pretty compelling.

Continue reading “Bare Metal Programming With Only Three Buttons”