Everyone loves NeoPixels. Individually addressable RGB LEDs at a low price. Just attach an Arduino, load the demo code, and enjoy your blinking lights.

But it turns out that demo code isn’t very efficient. [Ben Heck] practically did a spit take when he discovered that the ESP32 sample code for NeoPixels used a uint32 to store each bit of data. This meant 96 bytes of RAM were required for each LED. With 4k of RAM, you can control 42 LEDs. That’s the same amount of RAM that the Apollo Guidance Computer needed to get to the moon!

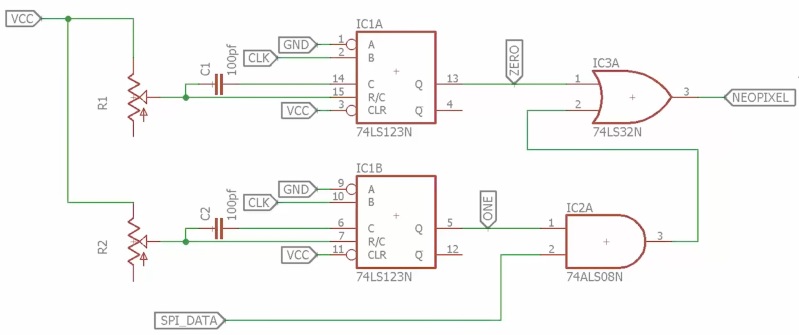

His adventure is based on the thought that you should be able to generate these signals with hardware SPI. First, he takes a look at Adafruit’s DMA-Driven NeoPixel example. While this is far more efficient than the ESP32 demo code, it still requires 3 SPI bits per bit of NeoPixel data. [Ben] eventually provides us with an efficient solution for SPI contro using a couple of 7400 series chips:

[Ben]’s solution uses some external hardware to reduce software requirements. The 74HC123 dual multi-vibrator is used to generate the two pulse lengths needed for the NeoPixels. The timing for each multi-vibrator is set by an external resistor and capacitor, which are chosen to meet the NeoPixel timing specifications.

The 74HC123s are clocked by the SPI clock signal, and the SPI data is fed into an AND gate with the long pulse. (In NeoPixel terms, a long pulse is a logical 1.) When the SPI data is 1, the long pulse is passed through to the NeoPixels. Otherwise, only the short pulse is passed through.

This solution only requires a 74HC123, an AND gate, and an OR gate. The total cost is well under a dollar. Anyone looking to drive NeoPixels with a resource-constrained microcontroller might want to give this design a try. It also serves as a reminder that some problems are better solved in hardware instead of software.

Continue reading “Inefficient NeoPixel Control Solved With Hardware Hackery”