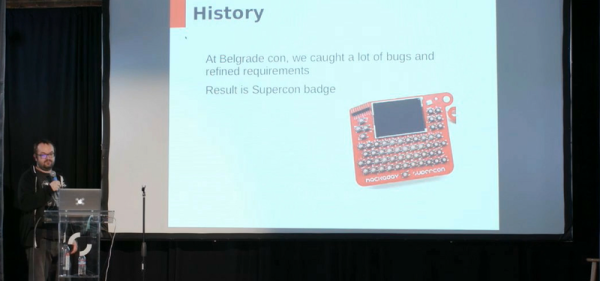

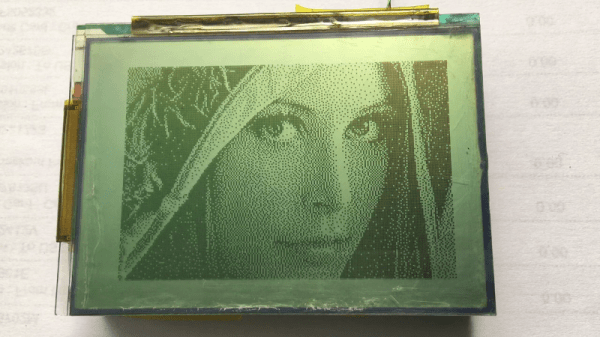

If you missed it, the Hackaday Supercon 2018 badge was a complete retro-minicomputer with a screen, keyboard, memory, speaker, and expansion ports that would make a TRS-80 blush. Only instead of taking up half of your desk, everyone at the conference had one around their neck, when they weren’t soldering to it, that is.

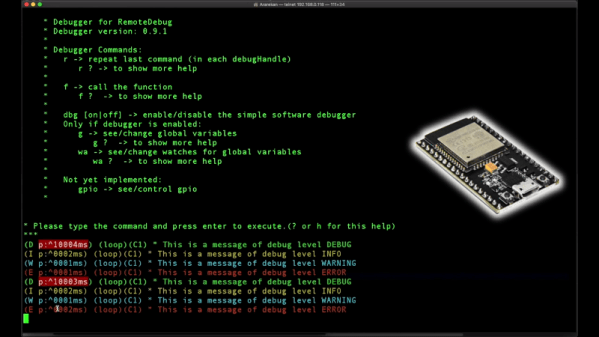

The killer feature of the badge was its accessibility and hackability — and a large part of that was due to the onboard BASIC interpreter. And that’s where Jaromir comes in. Once Voja Antonic had finalized the design of the badge hardware for our conference in Belgrade in the spring of 2018, as Jaromir puts it, “all we needed was a little bit of programming”. That would of course take three months. The badge was battle-tested in Belgrade, and various feature requests, speed ups, and bugfixes were implemented (during the con!) by Jaromir and others.

Firmware work proceeded over the summer. Ziggurat29 helped out greatly by finding ways to speed up the badge’s BASIC interpreter (that story is told on his UBASIC and the Need for Speed project page) and rolled into the code base by Jaromir. More bugs were fixed, keywords were added, and the three-month project grew to more like nine. The result: the badge was in great shape for the Supercon in the fall.

Jaromir’s talk about the badge is supremely short, so if you’re interested in hacking a retrocomputer into a PIC, or if you’ve got a badge and you still want to dig deeper into it, you should really give it a look. We don’t think that anyone fully exploited the CP/M machine emulator that lies inside — there’s tons of software written for that machine that is just begging to be run after all these years — but we’re pretty sure nearly everyone got at least into the basement in Zork. Dive in!

Continue reading “Jaromir Sukuba: The Supercon 2018 Badge Firmware”