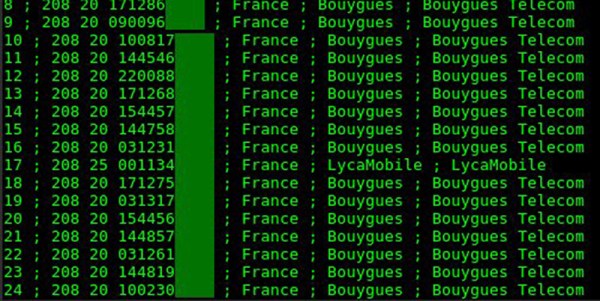

If there’s one thing that’s making you insecure, it’s your smartphone. Your smartphone is constantly pinging the cell towers, giving out your location and potentially leaking your private information to anyone with a radio. This is the idea behind an IMSI catcher, or Stingray in common parlance, and now you too can build one with parts you can buy off of Amazon.

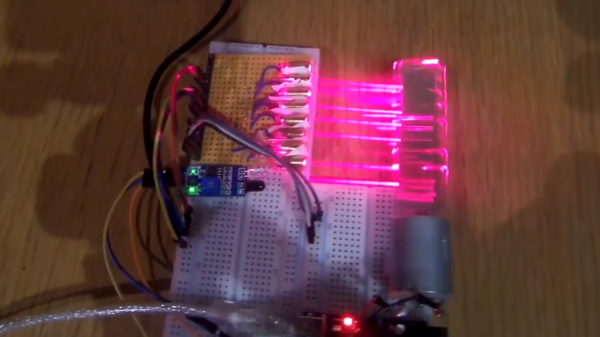

The key to this hack is a software defined radio dongle, or RTL-SDR, that has been repurposed to listen in on a GSM network. Literally the only hardware required is an RTL-SDR that can be bought online for less than fifteen dollars, and you can identify the IMSI, or unique ID linked to every SIM card, in smartphones around you. The only bit of software required is a small Python script from [Oros42], freely available on GitHub.

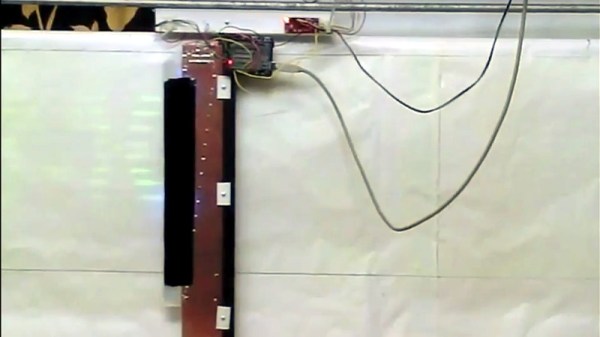

Of course, building an IMSI catcher with a desktop is of limited utility, and using a laptop is still a bit too bulky to surreptitiously conceal in a public location. No, to really get the bang for your buck out of this, you need to do this with a small single-board computer running off a battery pack. Luckily, [Joseph Cox] over at Motherboard reports, “It is likely possible” to run this on a Raspberry-Pi. We’re guessing it’s even more than “likely” possible.

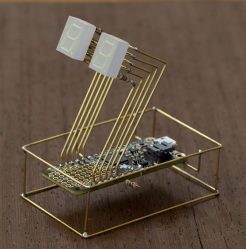

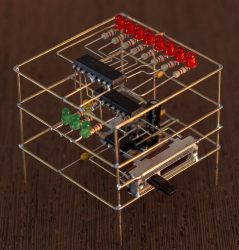

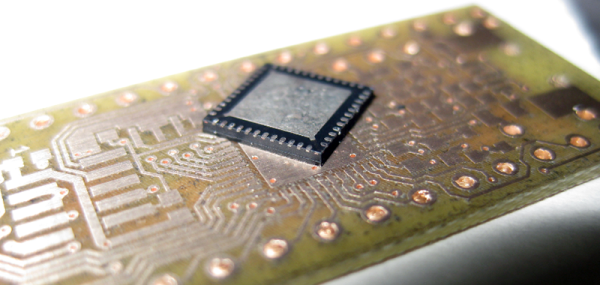

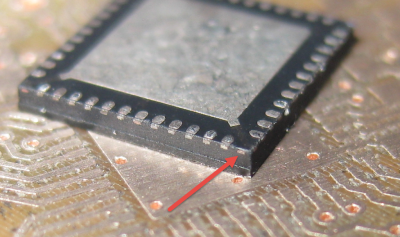

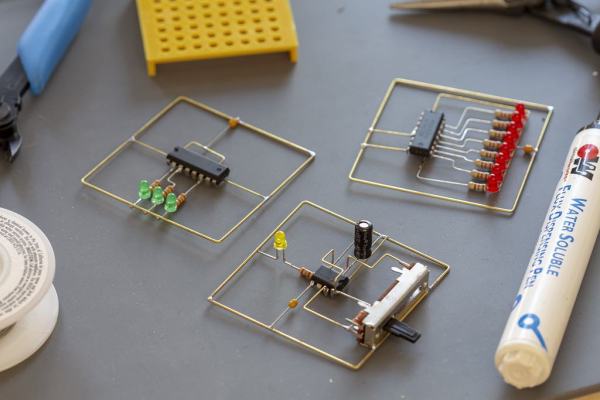

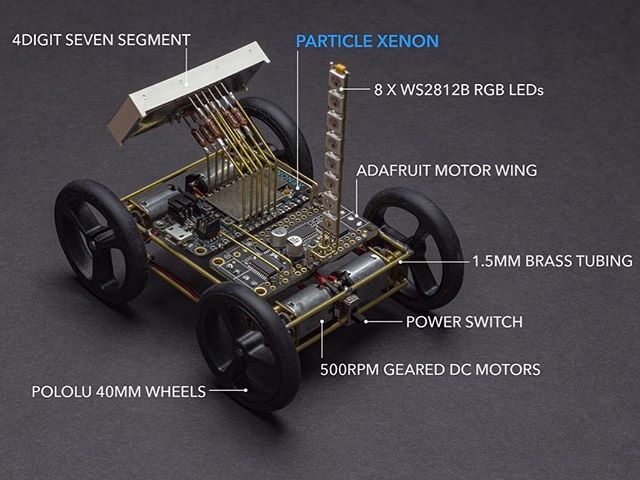

tiny BGA components (ok, that one might be more cool than practical). Perhaps our favorite use is to create art, and [Mohit Bhoite] is an absolute genius of the form. He’s so prolific that it’s difficult to point to a particular one of his projects as an exemplar, though he has

tiny BGA components (ok, that one might be more cool than practical). Perhaps our favorite use is to create art, and [Mohit Bhoite] is an absolute genius of the form. He’s so prolific that it’s difficult to point to a particular one of his projects as an exemplar, though he has