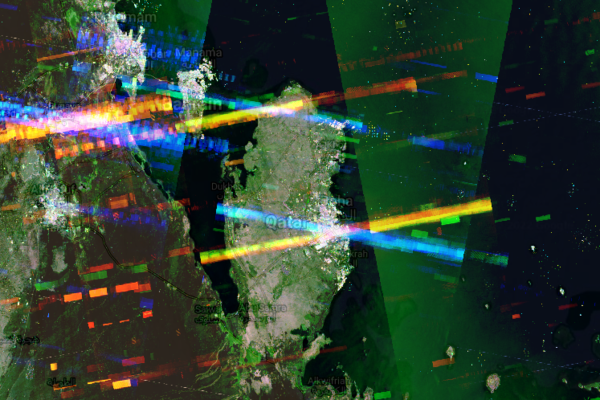

This week, Editor-in-Chief Elliot Williams and Assignments Editor Kristina Panos fumbled through setting up Mumble on Kristina’s new-ish computer box before hitting record and talking turkey. First off, we’ve got a fresh new contest going on, and this time it’s all about the FPVs. Then we see if Kristina can stump Elliot once again with a sound from her vast trove of ancient technologies.

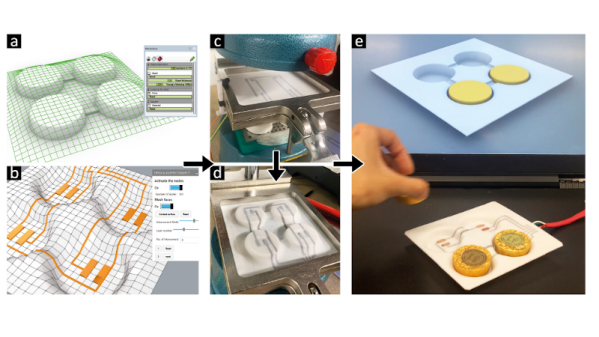

Then there’s much ado about coffee roasters of all stripes, and you know we’re both coffee enthusiasts. We have many words to say about the subject, but none of them are any of the 7+ dirty ones that the FCC would probably rather we didn’t. Finally, we take a look at a bike frame that’s totally nuts, a clock that seemingly works via magic, and a drone made of rice cakes. So find something to nibble on, and check out this week’s episode!

Download the podcast for safe keeping.

Check out the links below if you want to follow along, and as always, tell us what you think about this episode in the comments!

Continue reading “Hackaday Podcast 194: FPV Contest, Seven Words, Lots Of Coffee, And Edible Drones”