Microsoft made gaming history when it developed Achievements and released them with the launch of the Xbox 360. They have since become a key component of gaming culture, which similar systems rolling out to the rest of the consoles and even many PC games. [odelot] has the honor of being the one to bring this functionality to an odd home—the original Nintendo Entertainment System!

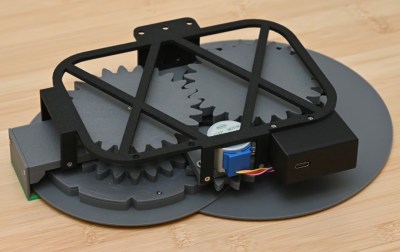

It’s actually quite functional, and it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds. What [odelot] created is the NES RetroAchievements (RA) Adapter. It contains a Raspberry Pi Pico which sits in between a cartridge and the console and communicates with the NES itself. The cartridge also contains an LCD screen, a buzzer, and an ESP32 which communicates with the Internet.

When a cartridge is loaded, the RA Adapter identifies the game and queries the RetroAchievements platform for relevant achievements for the title. It then monitors the console’s memory to determine if any of those achievements—such as score, progression, etc.—are met. If and when that happens, the TFT screen on the adapter displays the achievement, and a notification is sent to the RetroAchievements platform to record the event for posterity.

It reminds us of other great feats, like the MJPEG entry into the heart of the Sega Saturn.

Continue reading “Bringing Achievements To The Nintendo Entertainment System”