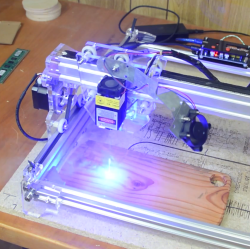

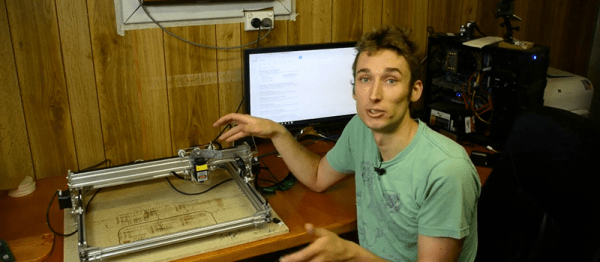

LaserWeb is open-source laser cutter and engraver software, and [JordsWoodShop] made a video tutorial (embedded below) on how to convert a cheap laser engraver to use it. The laser engraver used in the video is one of those economical acrylic-and-extruded-rail setups with a solid state laser emitter available from a variety of Chinese sellers (protective eyewear and any sort of ventilation or shielding conspicuously not included) but LaserWeb can work with just about any hardware, larger CO2 lasers included.

LaserWeb is open-source laser cutter and engraver software, and [JordsWoodShop] made a video tutorial (embedded below) on how to convert a cheap laser engraver to use it. The laser engraver used in the video is one of those economical acrylic-and-extruded-rail setups with a solid state laser emitter available from a variety of Chinese sellers (protective eyewear and any sort of ventilation or shielding conspicuously not included) but LaserWeb can work with just about any hardware, larger CO2 lasers included.

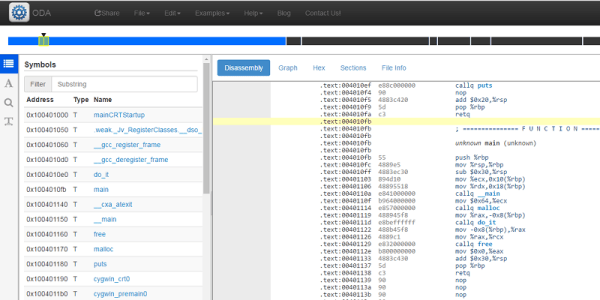

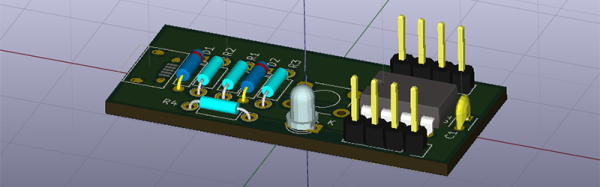

LaserWeb is important because most laser engravers and cutters have proprietary software. The smaller engravers like the one pictured above use a variety of things, and people experienced with larger CO2 laser cutters may be familiar with a piece of software called LaserCut — a combination CAD program and laser control that is serviceable, but closed (my copy even requires a USB security dongle, eww.)

LaserWeb allows laser engravers and cutters to be more like what most of us expect from our tools: a fully open-source toolchain. For example, to start using LaserWeb on one of those affordable 40 W blue-box Chinese laser cutters the only real hardware change needed is to replace the motion controller with an open source controller like a SmoothieBoard. The rest is just setting up the software and enjoying the added features.

Continue reading “Convert That Cheap Laser Engraver To 100% Open-Source Toolchain”

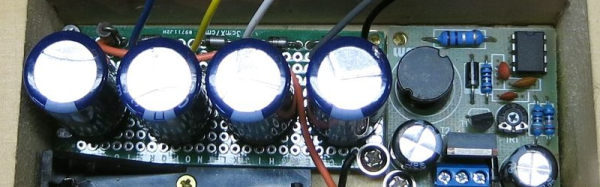

The project looks great. The wooden box apparently was a recycle item and the brass hardware makes it look like it belongs with the old radios it powers. This is a good example of how there’s more to vintage restoration than just the electronics. Sure, the function is important, but to really enjoy the old gear, the presentation is important, too.

The project looks great. The wooden box apparently was a recycle item and the brass hardware makes it look like it belongs with the old radios it powers. This is a good example of how there’s more to vintage restoration than just the electronics. Sure, the function is important, but to really enjoy the old gear, the presentation is important, too.