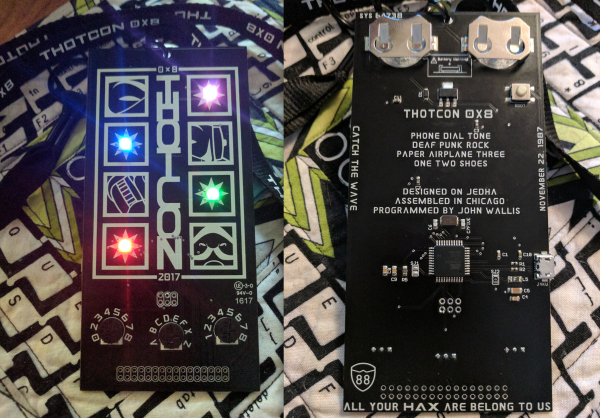

Designing pcbs for assembly is easy, right? We just squirt all the footprints onto a board layout, connect all the traces, send out the gerbers and position files, and we’re done–right?

Whoa, hold the phone, there, young rogue! Just like we can hack together some working source code with variables named after our best friends, we can also design our PCBs in ways that make it fairly difficult to assemble.

However, by following the agreed-upon design specs, we’ll put ourselves on track for success with automated assembly. If we want another party to put components on our boards, we need to clearly communicate the needed steps to get there. The best way to do so is by following the standards.

Proper Footprint Orientation

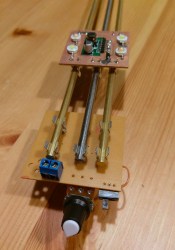

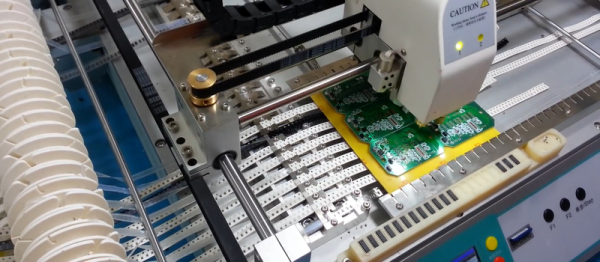

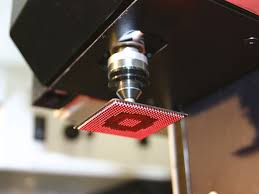

Now, for a mom ent, let’s imagine ourselves as the tip of a vacuum pickup tool on a pick-and-place machine. These tools are designed to pick up components on the reel from their centroid and plunk them on their corresponding land pattern. Seems pretty straightforward, right? It is, provided that we design our footprints knowing that they’ll one day come face-to-face with the pick-and-place machine.

ent, let’s imagine ourselves as the tip of a vacuum pickup tool on a pick-and-place machine. These tools are designed to pick up components on the reel from their centroid and plunk them on their corresponding land pattern. Seems pretty straightforward, right? It is, provided that we design our footprints knowing that they’ll one day come face-to-face with the pick-and-place machine.

To get from the reel to the board, we, the designers, need two bits of information from out part’s datasheet: the part centroid and the reel orientation.

The part centroid is an X-Y location that calls out the center-of-mass of the part. It basically tells the machine: “pick me up from here!” As designers, it’s our responsibility to design all of our footprints such that the footprint origin is set at the part’s centroid. If we forget to do so, the pick-and-place will try to suck up our parts from a location that may not stick very well to the package, such as: the corner.

Continue reading “Designing For Fab: A Heads-Up Before Designing PCBs For Professional Assembly” →