Integrated circuits are a fundamental part of almost all modern electronics, yet they closely resemble the proverbial “black box” – we may understand the inputs and outputs, but how many of us truly understand what goes on inside? Over the years, the process of decapping ICs has become popular – the removal of the package to enable peeping eyes to glimpse the mysteries inside. It’s an art that requires mastery of chemistry, microscopy and photography on top of the usual physics skills needed to understand electronics. Done properly, it allows an astute mind to reverse engineer the workings of the silicon inside.

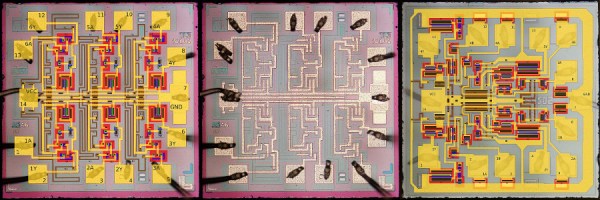

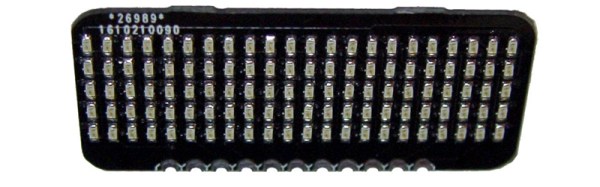

There are many out there publishing images of chips they’ve decapped, but [Robert Baruch] wants more. Namely, [Robert] seeks to create a database of die images of all 5400 and 7400 series logic chips – the eponymous Project 54/74.

These chips are the basic building blocks of digital logic – NAND gates, inverters, shift registers, decade counters and more. You can build a CPU with this stuff. These days, you may not be using these chips as often in a production context, but those of you with EE degrees will likely have toyed around a few of these in your early logic classes.

There’s only a handful of images up so far, but they’re of excellent quality, and they’re also annotated. This is a great aid if you’re trying to get to grips with the vagaries of chip design. [Robert] is putting in the hard yards to image as many variations of every chip as possible. There’s also the possibility of comparing the same chip for differences between manufacturers. We particularly like this project, as all too often manufacturing techniques and technologies are lost and forgotten as the march of progress continues on. It looks like it’s going to become a great resource for those looking to learn more about integrated circuit design and manufacture!