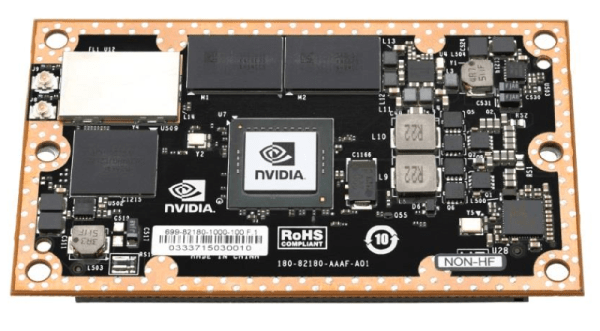

[DJI], everyone’s favorite — but very expensive — drone company just announced the Manifold — an extremely capable high performance embedded computer for the future of aerial platforms. And guess what? It runs Ubuntu.

The unit features a quad-core ARM Cortex A-15 processor with an NVIDIA Keplar-based GPU and runs Canonical’s Ubuntu OS with support for CUDA, OpenCV and ROS. The best part is it is compatible with third-party sensors allowing developers to really expand a drone’s toolkit. The benefit of having such a powerful computer on board means you can collect and analyze data in one shot, rather than relaying the raw output down to your control hub.

And because of the added processing power and the zippy GPU, drones using this device will have new artificial intelligence applications available, like machine-learning and computer vision — Yeah, drones are going to be able to recognize and track people; it’s only a matter of time.

We wonder what this will mean for FAA regulations…