Once you venture beyond the tame, comfortable walls of the 8-bit microcontroller world it can feel like you’re stuck in the jungle with a lot of unknown and oft scary hazards jut waiting to pounce. But the truth is that your horizons have expanded exponentially with the acceptable trade-off of increased complexity. That’s a pretty nice problem to have; the limitation becomes how much can you learn.

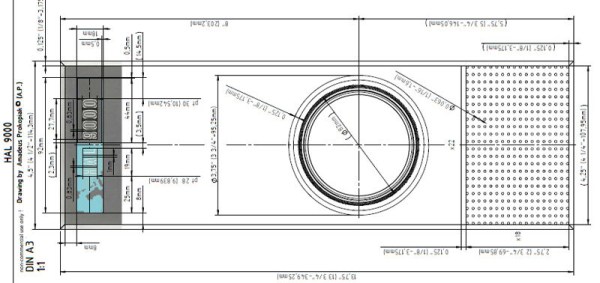

Here’s a great chance to expand your knowledge of the STM32 by learning more about the system clock options available. We’ve been working with STM32 chips for a few years now and still managed to find some interesting tidbits — like the fact that the High Speed External clock source accepts not just square waves but sine and triangle waves as well, and an interesting ‘gotcha’ about avoiding accidental overclocking. [Shawon M. Shahryiar] even covers one of our favorite subjects: watchdog timers (of which there are two different varieties on this chip). Even if this is not your go-to 32-bit chip family, most chips have similar clock source features so this reading will help give you a foothold when reading other datasheets.

There is a clock diagram at the top of that post which is small enough to be unreadable. You can get a better look at the diagram on page 12 of this datasheet. Oh, and just to save you the hassle of commenting on it, the chip shown above is not an f103… but it just happened to be sitting on our desk when we started writing.