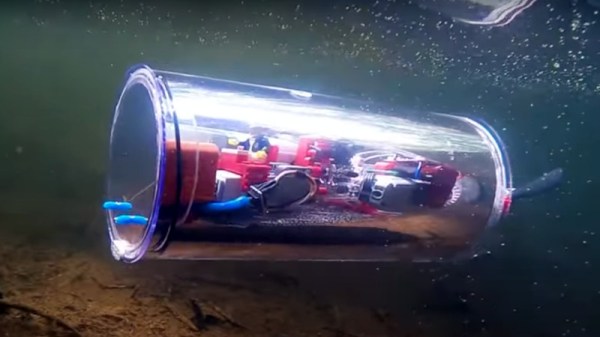

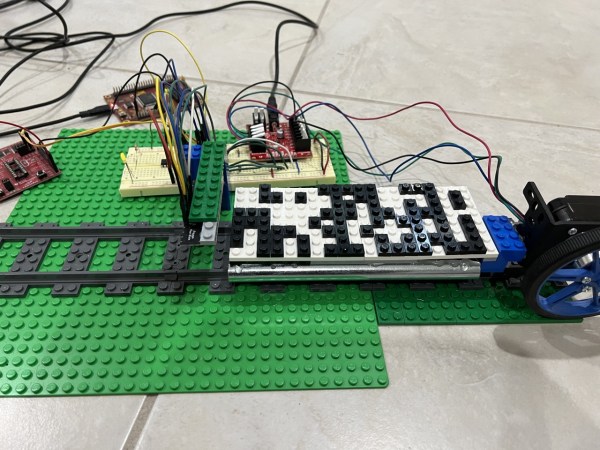

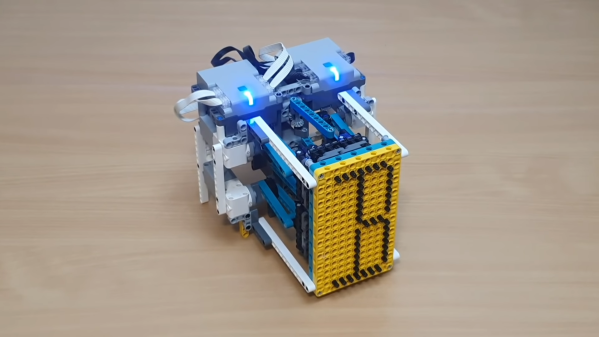

A submarine is by necessity a complex and safety-critical machine, but the principle upon which it depends is quite simple. The buoyancy is variable by means of pumping water in and out of tanks, allowing the craft to control the depth at which it sits. The [Brick Experiment Channel] has a series of posts describing in detail the construction of a working submarine, with a hull made from a plastic tube and mechanics made from Lego.

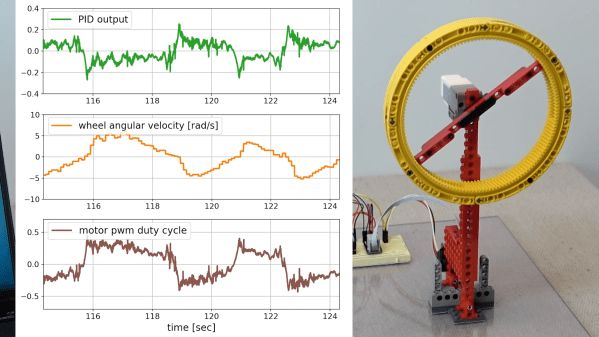

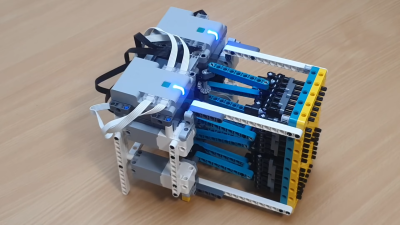

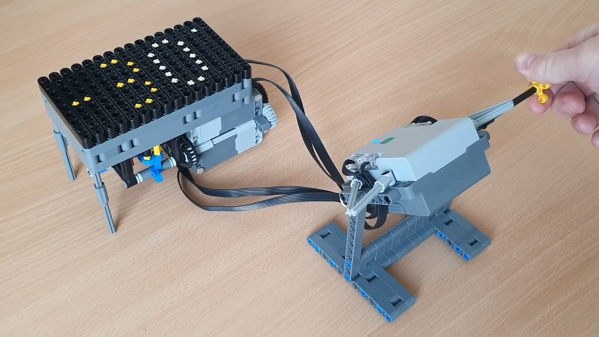

In this submarine the buoyancy tank is a syringe operated by a Lego motor, and the propulsion comes courtesy of a pair of Lego motors driven through ingenious magnetic couplings to avoid a shaft seal. To monitor depth there is both a laser distance sensor and a pressure sensor, and there is a Raspberry Pi Zero to control the whole show.

In the video below the break you can see the craft in action as it zips around a swimming pool at different depths, before setting off on a longer journey with on-board footage along a shady creek. It’s an extremely practical submarine, and one we wish we could try.

This is version 4.0, and it shows. We had a look at version 3.0 last year, and it’s by no means the first submarine we’ve featured, here’s one made from PVC pipe.