While there’s always the edge case, there’s a strong likelihood that if you’re using OpenSCAD, you’re probably working on a CAD model that you intend to 3D print at some point. Of course that’s not to say this is all you can do in OpenSCAD, but it’s arguably what it does best. If you wanted to make artistic models, or maybe render what your new kitchen will look like, there are other tools better suited to such tasks.

But thanks to lasercut.scad, a library that [Brendan Sleight] has been working on for the last several years, we might have to reconsider our preconceived dimensional notions. Instead of designing parts for 3D printing, his library is all about creating parts intended for subtractive manufacturing. Originally (as the name implies) it was geared towards laser cutting, but the project has since evolved to support CNC routers, vinyl cutters, and pretty much anything else that can follow a DXF file.

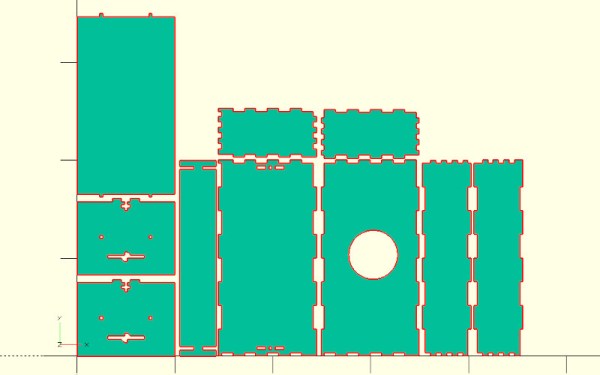

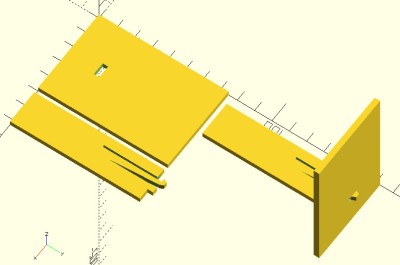

The library has functions for creating the standard tricks used to build things from laser-cut pieces, like finger joints, captive nuts, and assembly tabs. If it was something you once saw holding together an old wooden 3D printer kit back in the day, you can probably recreate it with lasercut.scad. It even supports a pretty wild piece of rotational joinery, courtesy of [Martin Raynsford].

Don’t have a way of concentrating a sufficient number of angry photons at your workpiece? No worries. The library has since been adapted to take into account a parametric kerf width, which lets you dial in how much of a bite your particular tool will take from the material when it does the business. There are even special functions for dealing with very thin cuts, which [Brendan] demonstrates by assembling a box from sheet vinyl.

Of course, those who’ve used OpenSCAD will know there’s not an “Export for CNC” button anywhere in the stock interface. So to actually take your design and produce a file your cutter can understand, [Brendan] has included a Bash script that will run the necessary OpenSCAD incantations to produce a 2D DXF file.

[Brendan] decided to send this one in after he saw the aluminum enclosure OpenSCAD library we covered recently. If you’ve got your own pet project that bends some piece of hardware or software to your will, don’t be shy to let us know.