I’ve designed a few M.2 adapters for my own and my friends’ use, and having found those designs online, people have asked me for custom-made adapters. One of these requests is quite specific – an adapter that adds one more PCIe link to an E-key M.2 slot, the kind of slot you will see used in laptops for WiFi cards.

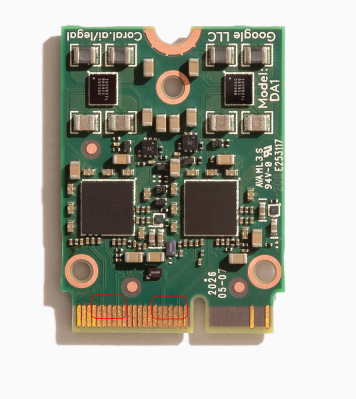

See, the M.2 specification allows two separate PCIe links connected to the E-key slot; however, no WiFi cards use this apart from some really old WiGig-capable ones, and manufacturers have long given up on connecting a second link. Nevertheless, there are some cards like the Google Coral M.2 E-key dual AI accelerator and the recently announced uSDR, that do indeed require the second link – otherwise, only half of their capacity is available.

It’s not clear why both Google and WaveletSDR designed for a dual-link E-key socket, since those are a rare occurrence; for the Google card, there are plenty of people complaining that the board they bought just doesn’t fully work. In theory, all you need to do to help such a situation, is getting a second PCIe link from somewhere, then wiring it up to the socket – and a perfect way to do it is to get a PCIe switch chip. You will lose out on some bandwidth because the uplink PCIe connection of the switch can only go so fast; for things like this AI accelerator, it’s not much of a problem since the main point is to get the second device accessible. For the aforementioned SDR, it might turn out useless, or you might win some but lose some – can’t know until you try! Continue reading “PCIe For Hackers: An M.2 Card Journey”