Every once in a while a project comes along with that magical power to consume your time and attention for many months. When you finally complete it, you feel sorry that you don’t have to do anything more.

What is so special about this Bingo ball reader? It may seem like an ordinary OCR project at first glance; a camera captures the image and OCR software recognizes the number. Simple as that. And it works without problems, like every simple gadget should.

But then again, maybe it’s not that simple. Numbers are scattered all over the ball, so they have to be located first, and the best candidate for reading must be selected. Then, numbers are painted onto a sphere rather than a flat surface, sometimes making them deformed to the point where their shape has to be recovered first. Also, the angle of reading is not fixed but somewhere on a 360° scale. And then we have the glare problem to boot, as Bingo balls are so shiny that every light source reflects as a saturated bright spot.

So, is that all of it? Well, almost. The task is supposed to be performed by an embedded microcontroller, with limited speed and memory, yet the recognition process for one ball has to be fast — 500 ms at worst. But that’s just one part of the process. The project includes the pipelined mechanism which accepts the ball, transports it to be scanned by the OCR and then shot by the public broadcast camera before it gets dumped. And finally, if the reading was not reliable enough, the ball has to be subtly rotated so that the numbers would be repositioned for another reading attempt.

Despite these challenges I did manage to build this system. It’s fast and reliable, and I discovered some very interesting tricks along the way. Take a look at the quick demo video below to get a feel for the speed, and what the system “sees”. Then join me after the break to dive into the details of this interesting embedded build.

Continue reading “Reading Bingo Balls With Microcontrollers”

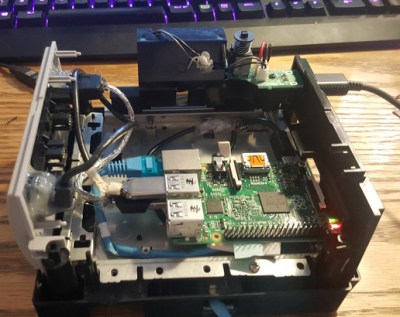

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.

Time marches on, and after a while, the Raspberry Pi 2 was released. By this time, retro emulation was hitting the big time, and [Liam] decided it was time for an upgrade. He disassembled this Nintendo console again, routed new wires and inputs to the original controller ports, and used a Dremel to route a few holes for the HDMI and SD card slot.