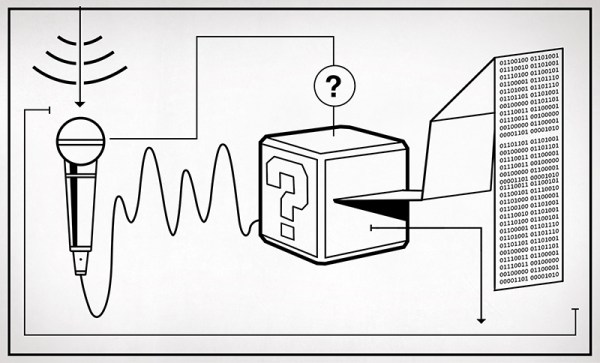

An interesting detail about the Intel 8087 floating point processor (FPU) is that it’s a co-processor that shares a bus with the 8086 or 8088 CPU and system memory, which means that somehow both the CPU and FPU need to know which instructions are intended for the FPU. Key to this are eight so-called ESCAPE opcodes that are assigned to the co-processor, as explained in a recent article by [Ken Shirriff].

The 8087 thus waits to see whether it sees these opcodes, but since it doesn’t have access to the CPU’s registers, sharing data has to occur via system memory. The address for this is calculated by the CPU and read from by the CPU, with this address registered by the FPU and stores for later use in its BIU register. From there the instruction can be fully decoded and executed.

This decoding is mostly done by the microcode engine, with conditional instructions like cos featuring circuitry that sprawls all over the IC. Explained in the article is how the microcode engine even knows how to begin this decoding process, considering the complexity of these instructions. The biggest limitation at the time was that even a 2 kB ROM was already quite large, which resulted in the 8087 using only 22 microcode entry points, using a combination of logic gates and PLAs to fully implement the entire ROM.

Only some instructions are directly implemented in hardware at the bus interface (BIU), which means that a lot depends on this microcode engine and the ROM for things to work half-way efficiently. This need to solve problems like e.g. fetching constants resulted in a similarly complex-but-transistor-saving approach for such cases.

Even if the 8087 architecture is convoluted and the ISA not well-regarded today, you absolutely have to respect the sheer engineering skills and out-of-the-box thinking of the 8087 project’s engineers.