A ukulele is a great instrument to pick to learn to play music. It’s easy to hold, has a smaller number of strings than a guitar, is fretted unlike a violin, isn’t particularly expensive, and everything sounds happier when played on one. It’s not without its limited downsides, though. Like any stringed instrument some amount of muscle memory is needed to play it fluidly which can take time to develop, but for new musicians there’s a handy new 3D printed part that can make even this aspect of learning the ukulele easier too.

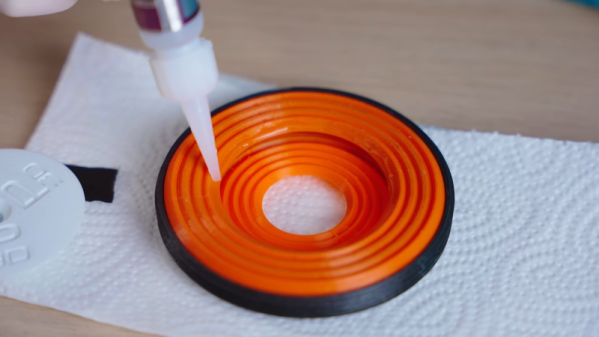

Called the Easy Fret, the tool clamps on to the neck of the ukulele and hosts a series of 3D printed “keys” that allow for complex chord shapes to be played with a single finger. In this configuration the chords C, F, G, and A minor can be played (although C probably shouldn’t be considered “complex” on a ukulele). It also makes extensive use of compliant mechanisms. For example, the beams that hit the chords use geometry to imitate a four-bar linkage. This improves the quality of the sound because the strings are pressed head-on rather than at an angle.

While this project is great for a beginner learning to play this instrument and figure out the theory behind it, its creator [Ryan Hammons] also hopes that it can be used by those with motor disabilities to be able to learn to play an instrument as well. And, if you have the 3D printer required to build this but don’t have an actual ukulele, with some strings and tuning pegs you can 3D print a working ukulele as well.