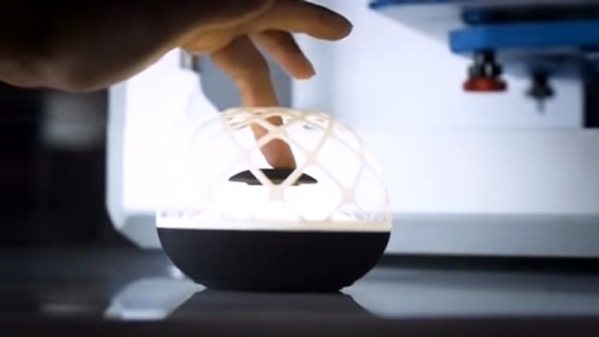

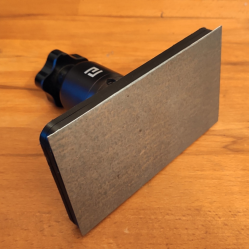

Flexible steel sheets as the foundation for build platforms are used to great advantage in FDM 3D printers. These coated sheets are held flat by magnets during printing, and after printing is done the sheet (with print attached) can be removed and flexed to pop the prints free. This got [Jan Mrázek] thinking. He was pretty sure the concept could extend to the build platform on his Elegoo Mars resin printer. With a flexible build platform, troublesome prints could be more easily removed, so he non-destructively modified his printer to have a similar system. [Jan] is clear that this is only a proof of concept, but the test results were good! He printed several jobs that were known to be trouble, and they were all a piece of cake to remove.

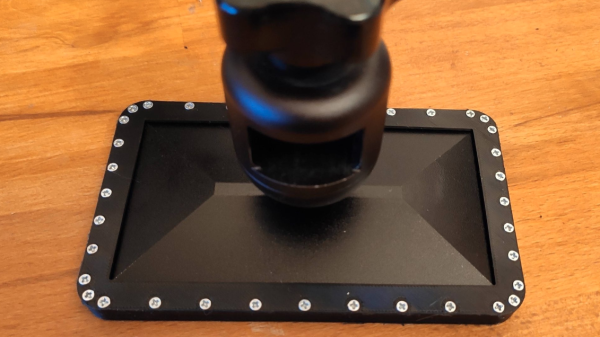

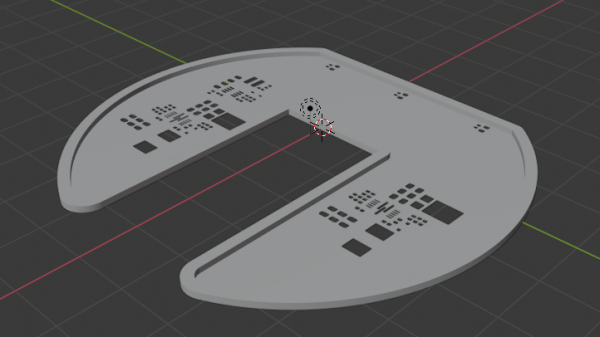

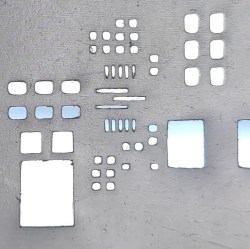

[Jan]’s mod consists of a 3D printed, two-piece unit that encapsulates the normal build platform and contains a few strong magnets. A thin sheet of steel sticks flat to this new piece, held in place by the magnets within, and becomes the new build platform. After a print is done, the sheet is removed and [Jan] reports that its flexibility is a big help in removing otherwise troublesome prints, such as the 3D printed solder stencil we covered recently.

[Jan]’s mod consists of a 3D printed, two-piece unit that encapsulates the normal build platform and contains a few strong magnets. A thin sheet of steel sticks flat to this new piece, held in place by the magnets within, and becomes the new build platform. After a print is done, the sheet is removed and [Jan] reports that its flexibility is a big help in removing otherwise troublesome prints, such as the 3D printed solder stencil we covered recently.

[Jan] provides his CAD model but doesn’t really recommend using it for anything other than development work. Results were promising, but there are a number of drawbacks to the prototype. For one thing, it makes the build platform thicker and the Z-axis limit switch needs to be physically lowered in order to zero the unit. Also, the thicker build platform means the volume of resin the build tank can hold is reduced. Still, the idea clearly has merit and shows there absolutely is value in hardware having a hackable design.