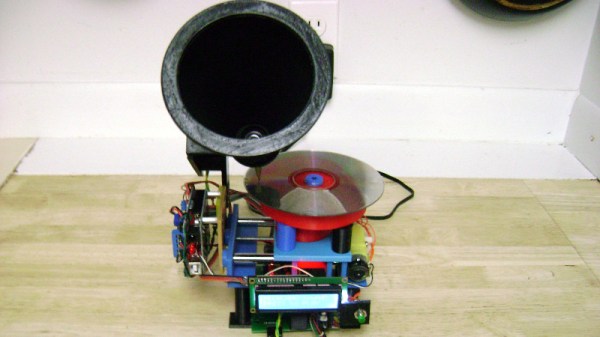

What happens to your 3D printer if the power goes out? What happens if there’s a jam in the nozzle? What happens if your filament breaks, runs out, or turns into a plate of spaghetti? For all these situations, the print fails, wasting plastic and time. For his Hackaday Prize entry, [robert] has come up with a tiny device that saves all those failed prints, and it does it without batteries or a UPS.

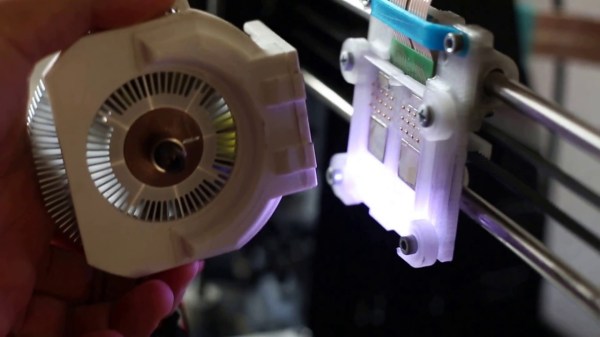

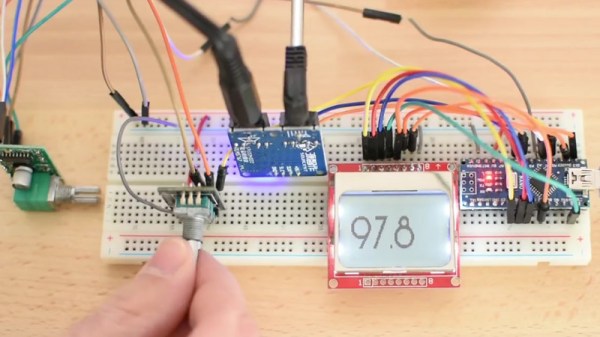

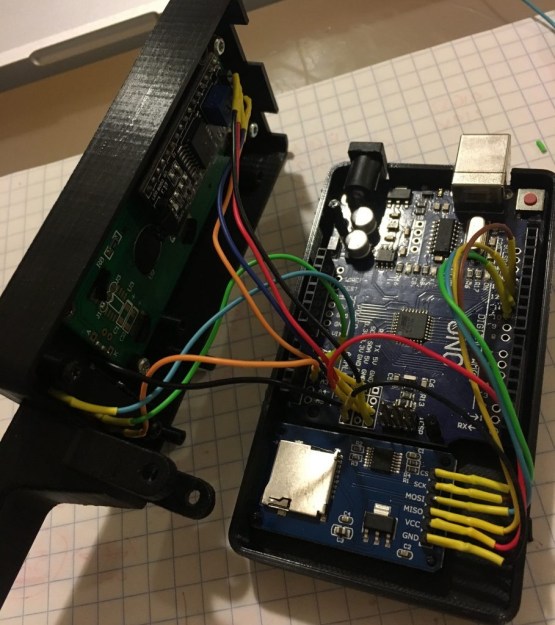

The idea behind [robert]’s box is to monitor all the G-code being sent to the printer, and allow a print to be resumed after a failure. The design is simple enough — just a USB mini port on one end, a USB A port on the other, and three buttons in between. This box logs the G-code, and if the printer happens to fail, the box will spring into life allowing you to resume a print from any Z position.

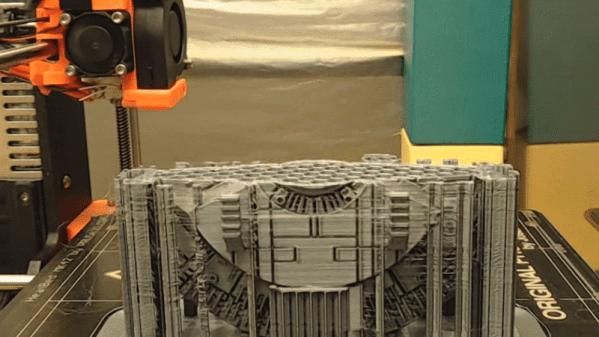

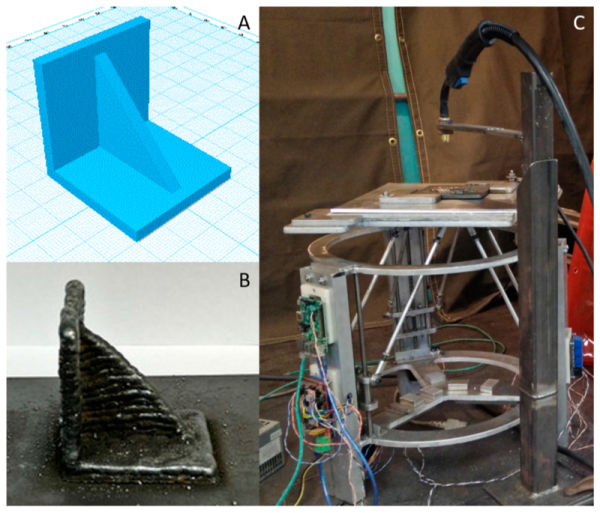

Already [robert] has tested this box on a number of printers including the Prusa i3, the Creality CR-10, and the ever-popular, explodey Anet A8. The project has already gone through a few hardware revisions and there is, of course, a fancy 3D printed enclosure for the board. It’s a great project, and one of the more interesting 3D printing tools we’ve seen in this year’s Hackaday Prize.