[Dave Akerman]’s interest in high-altitude projects means he is no stranger to long-range wireless communications, for which LoRa is amazingly useful. LoRa is a method of transmitting at relatively low data rates with low power over long distances.

[Dave Akerman]’s interest in high-altitude projects means he is no stranger to long-range wireless communications, for which LoRa is amazingly useful. LoRa is a method of transmitting at relatively low data rates with low power over long distances.

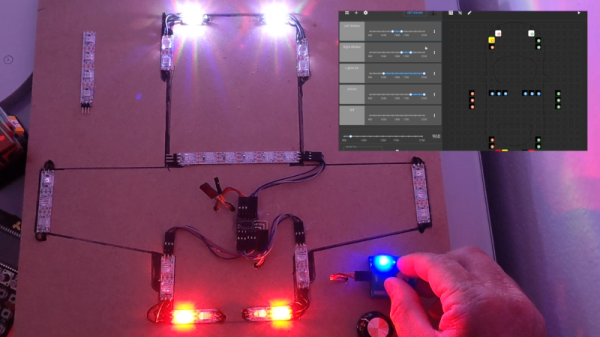

Despite LoRa’s long range, sometimes the transmissions of a device (like a balloon’s landed payload) cannot be received directly because it is too far away, or hidden behind buildings and geography. In these cases a useful solution is [Dave]’s self-contained LoRa repeater. The repeater hardware is simple, and [Dave] says that if one has the parts on hand, it can be built in about an hour.

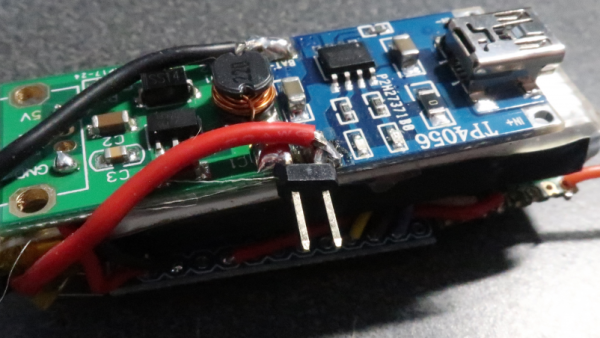

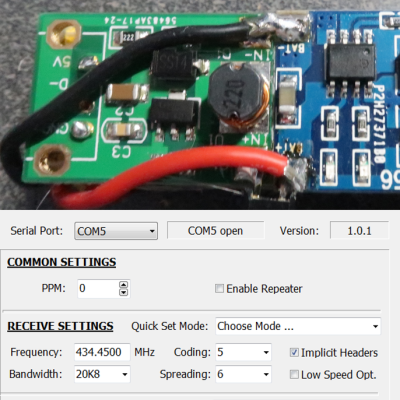

The device simply re-transmits any telemetry packets it receives, and all that takes is an Arduino Mini Pro and a small LoRa module. A tiny DC-DC converter, battery, and battery charger rounds out the bill of materials to create a small and self-contained unit that can be raised up on a mast, flown on a kite, or carried by a drone.

The repeater’s frequency and other settings can even be reprogrammed (using a small windows program) for maximum flexibility, making the little device invaluable when going hunting for landed payloads like the one [Dave] used to re-create a famous NASA image using a plastic model and a high-altitude balloon. Check out the details on the GitHub repository for the project and start mashing “add to cart” for parts at your favorite reseller.