We’re still not sure exactly how [connornishijima]’s motion detector works, though many readers offered plausible explanations in the comments the last time we covered it. It works well enough, though, and he’s gone and doubled down on the Arduino way and bundled it up nicely into a library.

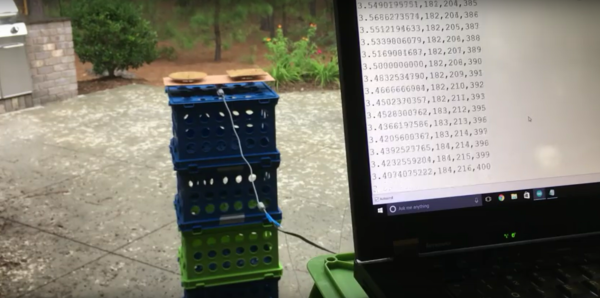

In the previous article we covered [connor] demonstrating the motion detector. Something about the way the ADC circuit for the Arduino is wired up makes it work. The least likely theory so far involves life force, or more specifically, the Force… from Star Wars. The most likely theories are arguing between capacitance and electrostatic charge.

Either way, it was reliable enough a phenomenon that he put the promised time in and wrote a library. There’s even documentation on the GitHub. To initialize the library simply tell it which analog pin is hooked up, what the local AC frequency is (so its noise can be filtered out), and a final value that tells the Arduino how long to average values before reporting an event.

It seems to work well and might be fun to play with or wow the younger hackers in your life with your wizarding magics.