It wasn’t that long ago that talking to computers was the preserve of movies and science fiction. Slowly, voice recognition improved, and these days it’s getting to be pretty usable. The technology has moved beyond basic keywords, and can now parse sentences in natural language. [Liz Meyers] has been working with the technology, creating WhatIsThat – an AI that can tell you what it’s looking at.

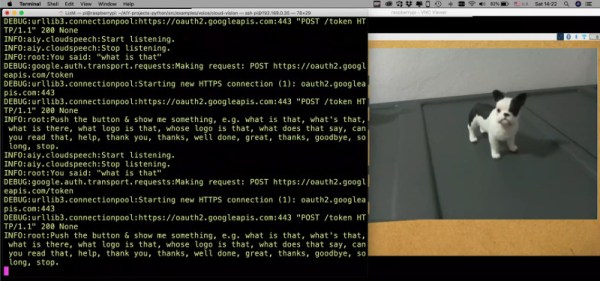

The device is built around Google’s AIY Voice Kit, which consists of a Raspberry Pi with some additional hardware and software to enable it to process voice queries. [Liz] combined this with a Raspberry Pi camera and the Google Cloud Vision API. This allows WhatIsThat to respond to users asking questions by taking a photo, and then identifying what it sees in the frame.

It may seem like a frivolous project to those with working vision, but there is serious potential for this technology in the accessibility space. The device can not only describe things like animals or other objects, it can also read text aloud and even identify logos. The ability of the software to go beyond is impressive – a video demonstration shows the AI correctly identifying a Boston Terrier, and attributing a quote to Albert Einstein.

Artificial intelligence has made a huge difference to the viability of voice recognition – because it’s one thing to understand the words, and another to understand what they mean when strung together. Video after the break.

[Thanks to Baldpower for the tip!]

Continue reading “This Cardboard Box Can Tell You What It Sees”