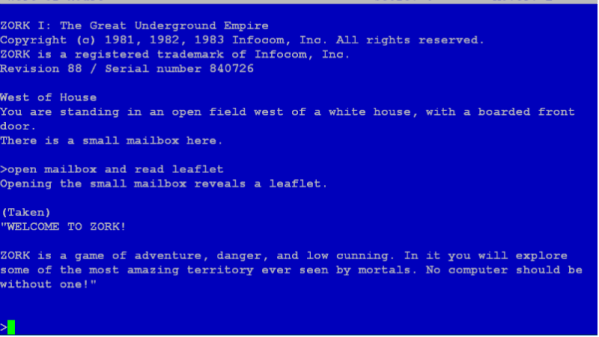

Before computer games had all these fancy graphics, text based games were a very popular genre. Rather than move a character on the screen, you’d type out commands for your player in sentence form which the game would interpret; decades before the “cloud” language processing technology that the likes of Amazon and Google currently use to power their virtual assistants. In some ways the genre was ahead of its time, but it didn’t survive the graphical revolution for home computers. Of course, these games still have some diehard fans out there.

[Dan The Geek] is one such fan. He loves text based adventure games like Zork so much that he wanted to create his own implementation of the core technology that made these games possible all those years ago. But he didn’t want to just do it on this desktop computer, there’s already projects that let you run these classic games on modern hardware. He wanted to see if he could run these classic games on a modern microcontroller, and create a authentic retro experience on a handy portable device.

[Dan The Geek] is one such fan. He loves text based adventure games like Zork so much that he wanted to create his own implementation of the core technology that made these games possible all those years ago. But he didn’t want to just do it on this desktop computer, there’s already projects that let you run these classic games on modern hardware. He wanted to see if he could run these classic games on a modern microcontroller, and create a authentic retro experience on a handy portable device.

[Dan] starts by explaining the technology used to make titles like these possible in the days when the wide array of home computer types required a nuanced approach. By separating the story files from the actual interpreter, developers could more easily port the games to various computers. In theory these interpreters, known as “Z-machines”, could be written for any computer that could compile C code, had enough RAM to hold the story, and had a terminal and keyboard. Not exactly the kind of system requirements we’re used to seeing for modern PC games, but it was the 1980’s.

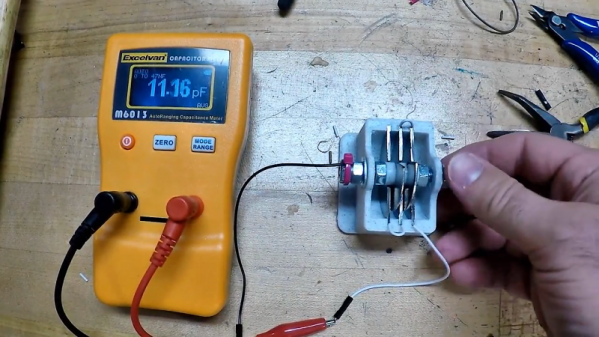

In theory a modern microcontroller will meet these requirements, so [Dan] wanted to create his own Z-machine for one. But rather than “cheat” by using an SD card like previous Arduino Z-machines have, he wanted to see if there was a development board out there that could do it all internally. The answer came in the form of the Adafruit ItsyBitsy M4 Express, with its 192 kB of RAM and 2 MB of SPI flash.

The Z-machine created by [Dan], which he’s calling A2Z, allows users to run Zork and other compatible interactive text games on the ItsyBitsy without any additional hardware. Just plug the board into your computer and you’ll be able to play the games over the the serial connection. He’s even implemented some retro color schemes to make the experience more authentic, like the blue of the Amiga or Compaq green.

We’ve covered previous projects that brought Zork and friends to the Arduino, your web browser via a virtual Altair 8800, and even some more exotic targets like custom FPGAs. You can play cave adventure, the game that inspired Zork, on the Supercon Badge.