We know, we know — yet another Nixie clock. But really, this one has a neat trick: an easy to use, feature packed driver for Nixies that makes good-looking projects a snap.

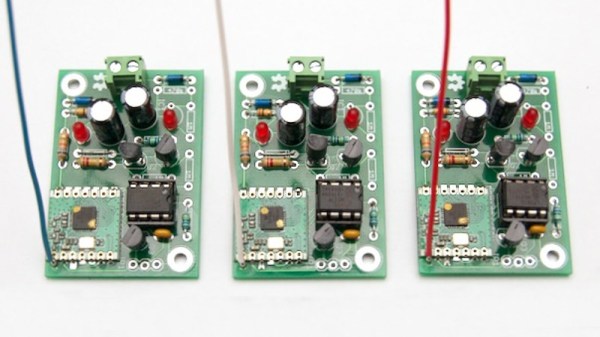

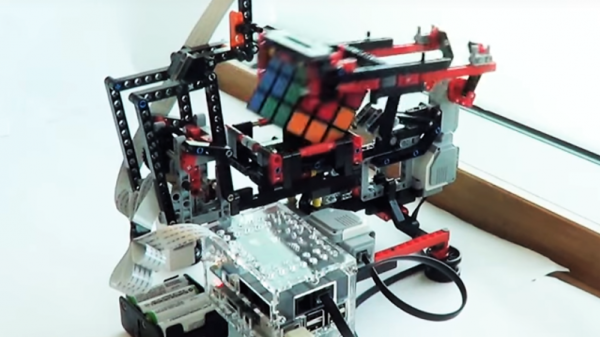

As cool as Nixies are — we’ll admit that to a certain degree, familiarity breeds contempt — they can be tricky to integrate. [dekuNukem] notes that aside from the high voltages, laying hands on vintage driver chips like the 7441 can be challenging and expensive. The problem was solved with about $3 worth of parts, including an STM32 microcontroller and some high-voltage transistors. The PCBs come in two flavors, one for the IN-12 and one for the IN-14, and connections for the SPI interface and both high- and low-voltage supplies are brought out to header pins. That makes the module easy to plug into a motherboard or riser card. The driver supports overdriving to accommodate poisoned cathodes, 127 brightness levels for smooth dimming, and a fully adjustable RBG backlight under the tube. See the boards in action in the video below, which features a nicely styled, high-accuracy clock.

From Nixie tachs to Nixie IoT clocks, [dekuNukem]’s boards should make creative Nixie projects even easier. But if you’re trying to drive a Nixie Darth Vader, you’re probably on your own.