While the current generation of smartwatches have only been on the market for a few years, companies have been trying to put a computer on your wrist since as far back as the 80s with varying degrees of success. One such company was Seiko, who in 1984 unveiled the UC-2000: a delightfully antiquated attempt at bridging the gap between wristwatch and personal computer. Featuring a 4-bit CPU, 2 KB of RAM, and 6 KB of ROM, the UC-2000 was closer to a Tamagotchi than its modern day counterparts, but at least it could run BASIC.

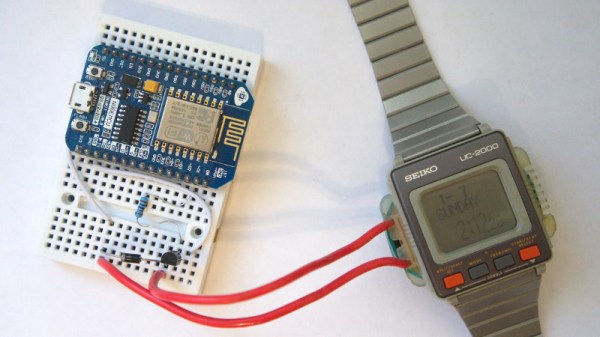

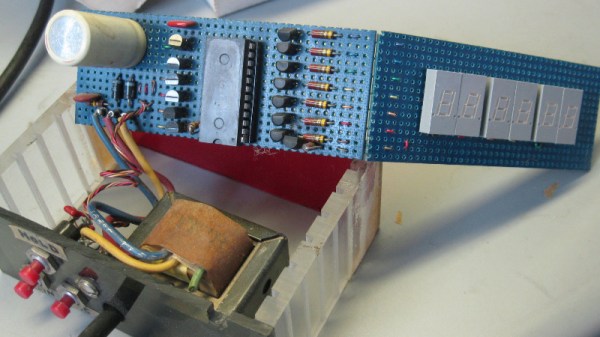

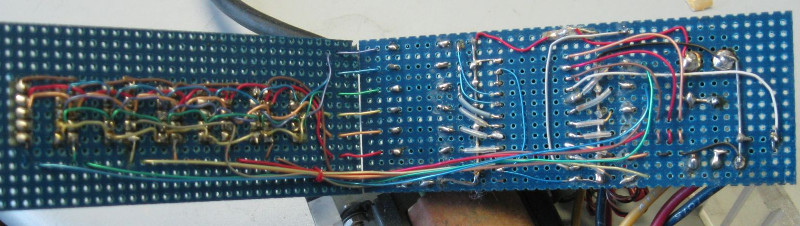

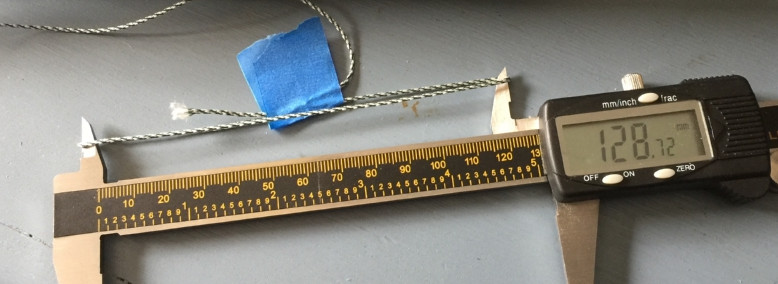

Ever since he saw the UC-2000 mentioned online, [Alexander] wanted to get one and try his hand at developing his own software for it. After securing one on eBay, the first challenge was getting it connected up to a modern computer. (Translated from Russian here.) [Alexander] managed to modernize the UC-2000’s novel induction based data transfer mechanism with help from a ATtiny85, which allowed him to get his own code on the watch, all that was left was figuring out how to write it.

With extremely limited published information, and no toolchain, [Alexander] did an incredible job of figuring out the assembly required to interact with the hardware. Along the way he made a number of discoveries which set his plans back, such as the fact that there is no way to directly control individual pixels on the screen; all graphics would have to be done with the built-in symbols.

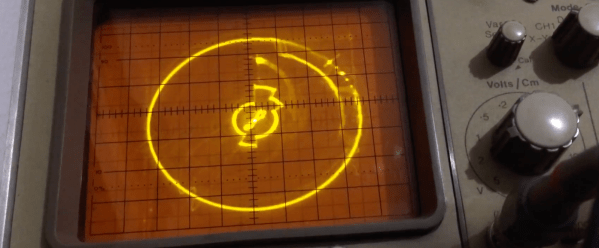

The culmination of all this hard work? Playing Tetris, naturally. Though [Alexander] admits that limitations of the device’s hardware meant the game had to be simplified a bit, he’s almost certainly having more fun than any of the UC-2000’s original owners did with this device. He’s setup a GitHub repository for anyone who wishes to join him in this brave new world of vintage wrist computing.

[Alexander] isn’t the only one experimenting with fringe wearable computers. We’ve seen our fair share of interesting smartwatches, featuring everything from novel input methods to complete scratch-builds.