Many moons ago, in the shadowy darkness of the 1990s, a young Lewin visited his elder cousin. An adept AMOS programmer, he had managed to get his Amiga 500 to control an RC car, with little more than a large pile of relays and guile. Everything worked well, but there was just one problem — once the car left the room, there was no way to see what was going on.

Why don’t you put a camera on it? Then you can drive it anywhere!

—Lewin

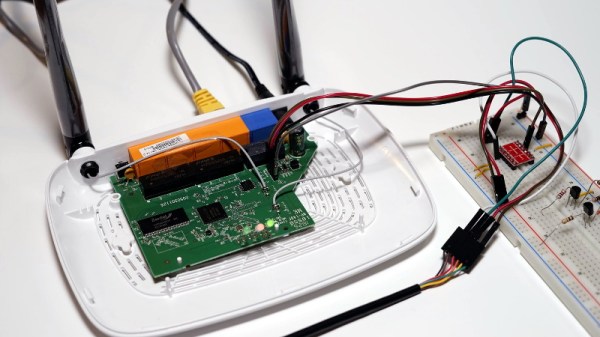

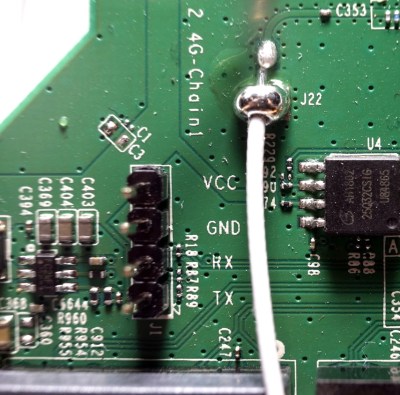

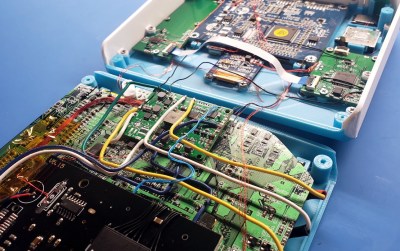

This would go on to inspire the TKIRV project approximately 20 years later. The goal of the project is to build a rover outfitted with a camera, which is controllable over cellular data networks from anywhere on Earth. For its upcoming major expedition, the vehicle is to receive solar panels to enable it to remain operable in distant lands for extended periods without having to return to base to recharge.

The project continues to inch towards this goal, but as the rover nears completion, the temptation to take it out for a spin grew ever greater. What initially began as an exciting jaunt actually netted plenty of useful knowledge for the rover’s further development.

Continue reading “A 4G Rover And The Benefits Of A Shakedown Mission”