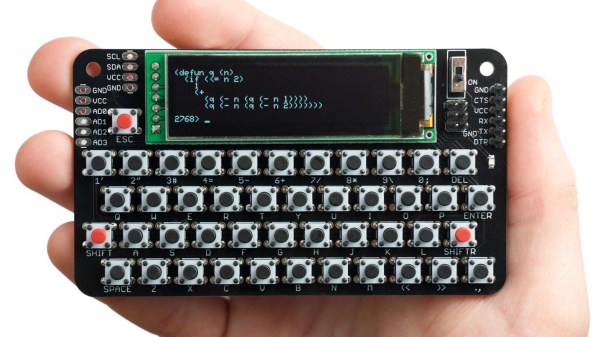

This hardware badge is a computer programmed with Lisp. You can write your own programs right on the badge using the built-in keyboard, as long as you know Lisp.

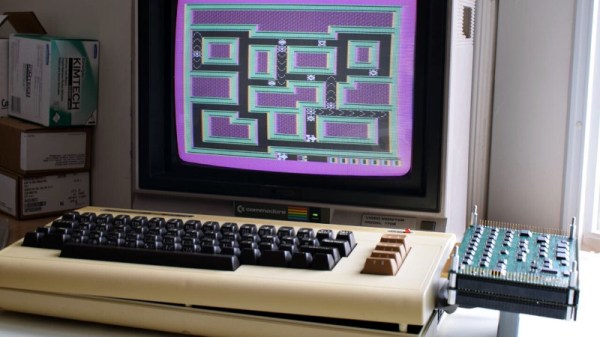

If there’s one thing we really like to see, it’s people advancing their own projects based on inspiration from others. The Lisp Badge by [David Johnson-Davies] is a perfect example. With an interface inspired by [Voja Antonic’s] hardware design for the 2018 Hackaday Belgrade Conference Badge, this version is an upgrade of an earlier single-board Lisp machine, now sporting an integrated keyboard.

Unlike the Belgrade badge, which is programmed in BASIC, this new badge is programmed in uLisp, a subset of common lisp designed for microcontrollers. Let’s face it, BASIC is retro, but Lisp is even more so, only pre-dated by FORTRAN as the oldest high-level language. So, if you’re into retro-style programming on small devices (physically small, that is), you should consider building one of these.

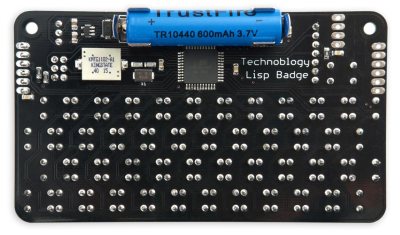

A 16 MHz ATmega 1284P serves as the badge’s brain, allowing storage for 2,816 Lisp cells, while the 256×64 pixel OLED display shows 8 lines of 42 characters in 16 gray levels. A full complement of I/O connections includes four analog inputs, two analog outputs, I2C, SPI, serial, and a handful of GPIOs for interfacing with just about anything. Power comes from a LiPO battery, which at a nominal voltage of 3.7 V doesn’t quite meet the datasheet requirements for running the processor at 16 MHz, although it seems to work fine in practice. Really cautious builders could opt for a 12 MHz crystal transplant to avoid any possibility of problems.

A 16 MHz ATmega 1284P serves as the badge’s brain, allowing storage for 2,816 Lisp cells, while the 256×64 pixel OLED display shows 8 lines of 42 characters in 16 gray levels. A full complement of I/O connections includes four analog inputs, two analog outputs, I2C, SPI, serial, and a handful of GPIOs for interfacing with just about anything. Power comes from a LiPO battery, which at a nominal voltage of 3.7 V doesn’t quite meet the datasheet requirements for running the processor at 16 MHz, although it seems to work fine in practice. Really cautious builders could opt for a 12 MHz crystal transplant to avoid any possibility of problems.

The keyboard layout is optimized for uLisp programming: unnecessary keys have been removed and the all-important parenthesis are afforded their own dedicated keys on the bottom row. This is presumably for convenience of use, but we suspect this will also make it easier to replace the parenthesis key switches when they inevitably wear out from overuse [obligatory Lisp/parenthesis joke].

As far as entering uLisp programs, you can simply use the keyboard. The built-in editor buffers a full screen of text, and includes parenthesis matching that highlights each pair as you type. We’re guessing that we won’t see Emacs implemented in the near future, so this bracket management is a great feature for a badge-based editor. If you find the keyboard difficult to type on, you can also enter programs over the serial port.

The other thing we really like to see is open-source projects. [David] doesn’t let us down on this point, either. The Eagle design files for the PCB as well as the source code for the badge are available on GitHub. The PCB is also shared on OSH Park, and there are detailed instructions for installing the bootloader and uploading the code.

If programmable badges is your thing, also check out the 2018 Hackaday Supercon Badge, the successor the Belgrade design.

Thanks to [Sven] for the tip!