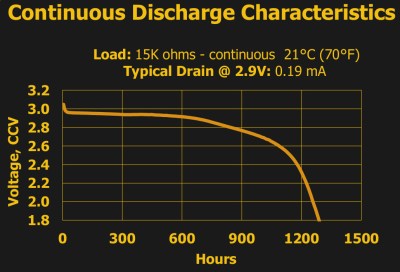

Some of the entries for the 2017 Coin Cell Challenge have already redefined what most would have considered possible just a month ago. From starting cars to welding metal, coin cells are being pushed way outside of their comfort zone with some very clever engineering. But not every entry has to drag a coin cell kicking and screaming into a task it was never intended for; some are hoping to make their mark on the Challenge with elegance rather than brute strength.

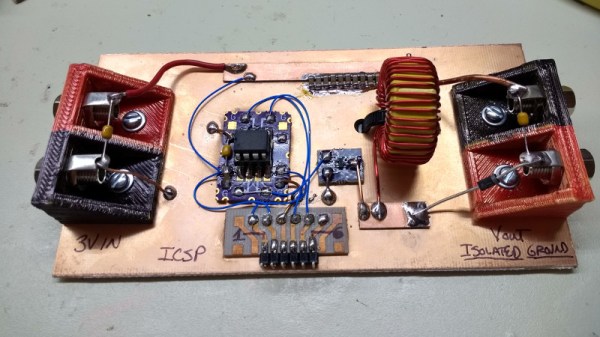

A perfect example is the LiquidWatch by [CF]. There’s no fancy high voltage circuitry here, no wireless telemetry. For this entry, a coin cell is simply doing what it’s arguably best known for: powering a wrist watch. But it’s doing it with style.

A perfect example is the LiquidWatch by [CF]. There’s no fancy high voltage circuitry here, no wireless telemetry. For this entry, a coin cell is simply doing what it’s arguably best known for: powering a wrist watch. But it’s doing it with style.

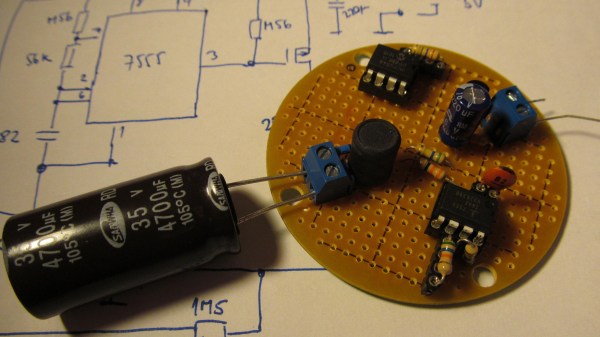

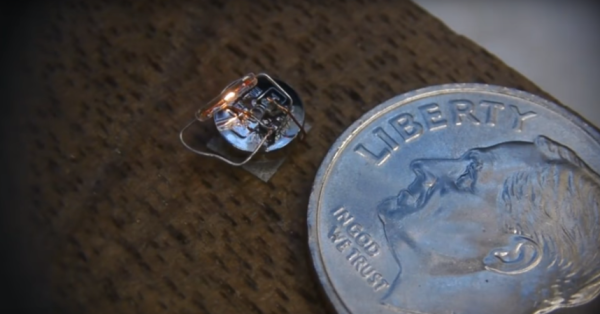

The LiquidWatch is powered by an Arduino-compatible Atmega328 and uses two concentric rings of LEDs to display the time. Minutes and seconds are represented by the outer ring of 60 LEDs, and the 36 LEDs of the inner ring show hours. The hours ring might sound counter-intuitive with 36 positions, but the idea is to think of the ring as the hour hand of an analog watch rather than a direct representation of the hour. Having 36 LEDs for the hour allows for finer graduation than simply having one LED for each hour of the day. Plus it looks cool, so there’s that.

Square and round versions of the LiquidWatch’s are in development, with some nice production images of [CF] laser cutting the square version out of some apple wood. The wooden case and leather band give the LiquidWatch a very organic vibe which contrasts nicely with the high-tech look of the exposed PCB display. Even if you are one of the legion that are no longer inclined to wear a timepiece on their wrist, you’ve got to admit this one is pretty slick.

Whether you’re looking to break new ground or simply refine a classic, there’s still plenty of time to enter your project in the 2017 Coin Cell Challenge.