On the face of it, keeping fluids contained seems like a simple job. Your fridge alone probably has a dozen or more trivial examples of liquids being successfully kept where they belong, whether it’s the plastic lid on last night’s leftovers or the top on the jug of milk. But deeper down in the bowels of the fridge, like inside the compressor or where the water line for the icemaker is attached, are more complex and interesting mechanisms for keeping fluids contained. That’s the job of seals, the next topic in our series on mechanisms.

Original Art1219 Articles

The King Of Machine Tools

The lathe is known as the King of Machine Tools for a reason. There are very few things that you can’t make with one. In fact, people love to utter the old saw that the lathe is the only machine tool that can make itself. While catchy, I think that’s a bit disingenuous. It’s more accurate to say that there are parts in all machine tools that (arguably) only a lathe can make. In that sense, the lathe is the most “fundamental” machine tool. Before you harbor dreams of self-replication, however, know that most of an early lathe would be made by hand scraping the required flat surfaces. So no, a lathe can’t make itself really, but a lathe and a skilled craftsperson with a hand-scraper sure can. In fact, if you’ve read the The Metal Lathe by David J. Gingery, you know that a lathe is instrumental in building itself while you’re still working on it.

We’re taking trip through the machining world with this series of articles. In the previous article we went over the history of machine tools. Let’s cut to the modern chase now and help some interested folks get into the world of hobby machining, shall we? As we saw last time, the first machine tools were lathes, and that’s also where you should start.

Vera Rubin: Shedding Light On Dark Matter

Vera sat hunched in the alcove at Kitt Peak observatory, poring over punch cards. The data was the same as it had been at Lowell, at Palomar, and every other telescope she’d peered through in her feverish race to collect the orbital velocities of stars in Andromeda. Although the data was perfectly clear, the problem it posed was puzzling. If the stars at the edges of spiral galaxy were moving as fast as the ones in the center, but the pull of gravity was weaker, how did they keep from flying off? The only possible answer was that Andromeda contained some kind of unseen matter and this invisible stuff was keeping the galaxy together.

Though the idea seemed radical, it wasn’t an entirely new one. In 1933, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky made an amazing discovery that was bound to bring him fame and fortune. While trying to calculate the total mass of the galaxies that make up the Coma Cluster, he found that the mass calculation based on galaxy speed was about ten times higher than the one based on total light output. With this data as proof, he proposed that much of the universe is made of something undetectable, but undeniably real. He dubbed it Dunkle Materie: Dark Matter.

But Zwicky was known to regularly bad mouth his colleagues and other astronomers in general. As a result, his wild theory was poorly received and subsequently shelved until the 1970s, when astronomer Vera Rubin made the same discovery using a high-powered spectrograph. Her findings seemed to provide solid evidence of the controversial theory Zwicky had offered forty years earlier.

Continue reading “Vera Rubin: Shedding Light On Dark Matter”

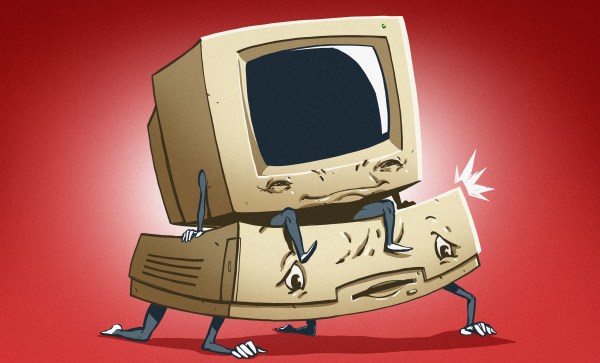

Whatever Happened To The Desktop Computer?

If you buy a computer today, you’re probably going to end up with a laptop. Corporate drones have towers stuffed under their desks. The cool creative types have iMacs littering their open-plan offices. Look around on the online catalogs of any computer manufacturer, and you’ll see there are exactly three styles of computer: laptops, towers, and all-in-ones. A quick perusal of Newegg reveals an immense variety of towers; you can buy an ATX full tower, an ATX mid-tower, micro-ATX towers, and even Mini-ITX towers.

It wasn’t always this way. Nerds of a sufficient vintage will remember the desktop computer. This was, effectively, a tower tilted on its side. You could put your monitor on top, negating the need for a stack of textbooks bringing your desktop up to eye level. The ports, your CD drive, and even your fancy Zip drive were right there in front of you. Now, those days of desktop computers are long gone, and the desktop computer is relegated to history. What happened to the desktop computer, and why is a case specifically designed for a horizontal orientation so hard to find?

Continue reading “Whatever Happened To The Desktop Computer?”

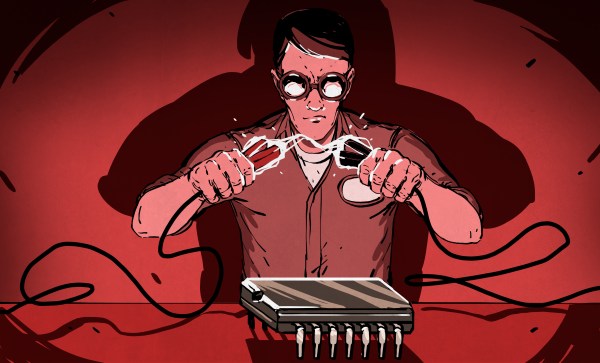

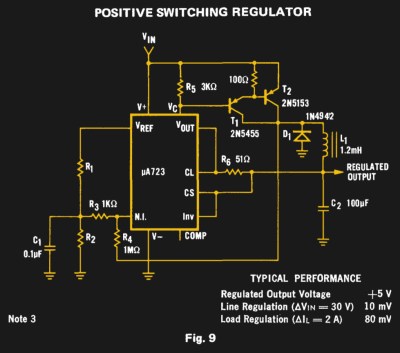

The UA723 As A Switch Mode Regulator

If you are an electronic engineer or received an education in electronics that went beyond the very basics, there is a good chance that you will be familiar with the Fairchild μA723. This chip designed by the legendary Bob Widlar and released in 1967 is a kit-of-parts for building all sorts of voltage regulators. Aside from being a very useful device, it may owe some of its long life to appearing as a teaching example in Paul Horowitz and Winfield Hill’s seminal text, The Art Of Electronics. It’s a favourite chip of mine, and I have written about it extensively both on these pages and elsewhere.

For all my experimenting with a μA723 over the decades there is one intriguing circuit on its data sheet that I have never had the opportunity to build. Figure 9 on the original Fairchild data sheet is a switching regulator, a buck converter using a pair of PNP transistors along with the diode and inductor you would expect. Its performance will almost certainly be eclipsed by a multitude of more recent dedicated converter chips, but it remains the one μA723 circuit I have never built. Clearly something must be done to rectify this situation.

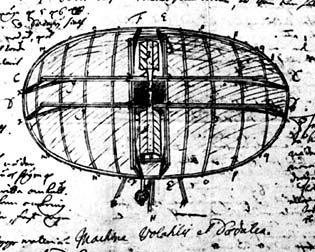

Hovercraft Of The Future

We think of hovercraft as a modern conveyance. After all, any vision of the future usually includes hovercraft or flying cars along with all the other things we imagine in the future. So when do you think the hovercraft first appeared? The 1960s? The 1950s? Maybe it was a World War II development from the 1940s? Turns out, a human-powered hovercraft was dreamed up (but not built) in 1716 by [Emanuel Swedenborg]. You can see a sketch from his notebook below. OK, that’s not fair, though. Imagining it and building one are two different things.

[Swedenborg] realized a human couldn’t keep up the work to put his craft on an air cushion for any length of time. Throughout the 1800s, though, engineers kept thinking about the problem. Around 1870, [Sir John Thornycroft] built several test models of ship’s hulls that could trap air to reduce drag — an idea called air lubrication, that had been kicked around since 1865. However, with no practical internal combustion engine to power it, [Thornycroft’s] patents didn’t come to much. In America, around 1876 [John Ward] proposed a lightweight platform using rotary fans for lift but used wheels to get forward motion. Others built on the idea, but they still lacked the engines to make it completely practical.

But even 1940 is way too late for a working hovercraft. [Dagobert Müller] managed that in 1915. With five engines, the craft was like a wing that generated lift in motion. It was a warship with weapons and a top speed of around 32 knots, although it never saw actual combat. Because of its physical limitations it could only operate over water, unlike more modern craft.

Mary Somerville: The First Scientist

Science, as a concept, is relatively new. Benjamin Franklin wasn’t a scientist probing the mysteries of amber and wool and electricity and ‘air baths’; he was a natural philosopher. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was simply a man with a proclivity towards creating new and novel instruments. Robert Hooke was a naturalist and polymath, and Newton was simply a ‘man of science’. None of these men were ever called ‘scientists’ in their time; the term hadn’t even been coined yet.

The word ‘scientist’ wouldn’t come into vogue until the 1830s. The word itself was created by William Whewell, reviewing The Connexion of the Physical Sciences by Mary Somerville. The term used at the time, ‘a man of science’, didn’t apply to Mrs. Somerville, and, truth be told, the men of science of the day each filled a particular niche; Faraday was interested in electricity, Darwin was a naturalist. Mary Somerville was a woman and an interdisciplinarian, and the word ‘scientist’ was created for her.