Though it suffered through decades of naysayers, these days you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who would still argue that the commercialization of space has been anything but a resounding success for the United States. SpaceX has completely disrupted what was a stagnant industry — of the 108 US rocket launches in 2023, 98 of them were performed by the Falcon 9. Even the smaller players, such as Rocket Lab and Blue Origin, are innovating and bringing new technologies to market at a rate which the legacy aerospace companies haven’t been able to achieve since the Space Race.

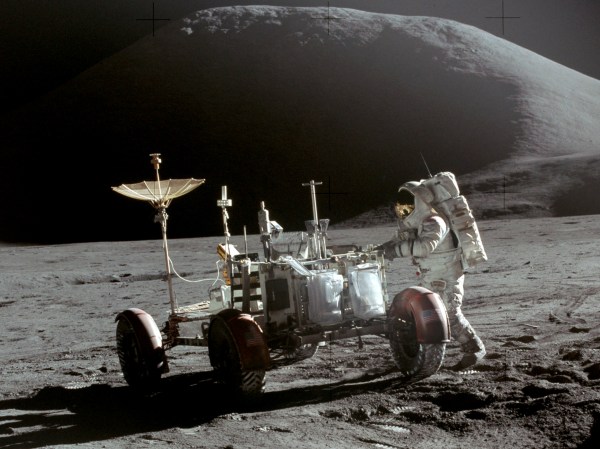

So it’s no surprise that other countries are looking to replicate that success. Japan in particular has been following NASA’s playbook by offering lucrative space contracts to major domestic tech companies such as Mitsubishi, Honda, NEC, Toyota, Canon, Kyocera, and Sumitomo. Over the last several years this has resulted in the development of a number spacecraft and missions, such as the Hakuto-R Moon lander. It’s also laid the groundwork for exciting future projects, like the crewed lunar rover Toyota and Honda are jointly developing for the Artemis program.

So it’s no surprise that other countries are looking to replicate that success. Japan in particular has been following NASA’s playbook by offering lucrative space contracts to major domestic tech companies such as Mitsubishi, Honda, NEC, Toyota, Canon, Kyocera, and Sumitomo. Over the last several years this has resulted in the development of a number spacecraft and missions, such as the Hakuto-R Moon lander. It’s also laid the groundwork for exciting future projects, like the crewed lunar rover Toyota and Honda are jointly developing for the Artemis program.

But so far there’s been a crucial element missing from Japan’s commercial space aspirations, an orbital booster rocket. While the country has state-funded launch vehicles such as the H-IIA and H3 rockets, they come with the usual bureaucracy one would expect from a government program. In comparison, a privately developed and operated booster holds the promise of reduced costs and a higher launch cadence, especially if there are multiple competing vehicles on the market.

With the recent test flight of Space One’s KAIROS rocket, that final piece of the puzzle may finally be falling into place. While the launch unfortunately failed shortly after liftoff, the fact that the private rocket was able to get off the ground — literally and figuratively — is a promising sign of what’s to come.

Continue reading “Japan’s First Commercial Rocket Debuts With A Bang”