There’s an uneasy meeting in the world of audio between digital and analogue. Traditional analogue audio reached a level of very high quality, but as old-style media-based audio sources have fallen out of favor there’s a need to replace them with ones that reflect a new digital audio world. To do this there are several options involving all-in-one Hi-Fi separates at a hefty price, a cheaper range of dongles and boxes for each digital input, or to do what [Keri Szafir] has done and build that all-in-one box for yourself.

The result is a 1U 19″ rack unit that contains an Orange Pi for connectivity and streaming, a hard drive to give it audio NAS capability, plus power switching circuitry to bring all the older equipment under automation. Good quality audio is dealt with by using a Behringer USB audio card, on which in a demonstration of how even some digital audio is now becoming outdated, she ignores the TOSlink connector.

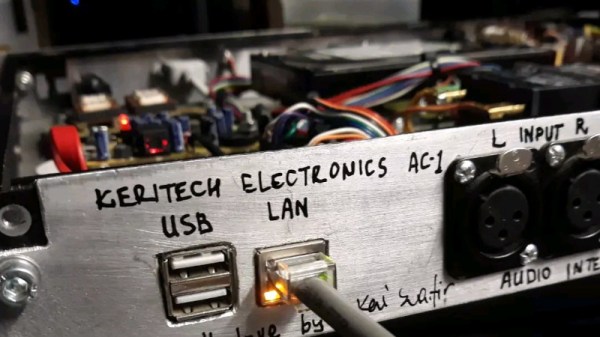

The rear panel has all the connectors for power, USB, network, and audio laid out, while the front has an array of status lights and switches. We particularly like the hand-written lettering, which complements this as a homebrew unit. It certainly makes the Bluetooth dongle dangling at the back of our amplifier seem strangely inadequate.

If audio is your thing, we had a look at some fundamentals of digital audio as part of our Know Audio series.