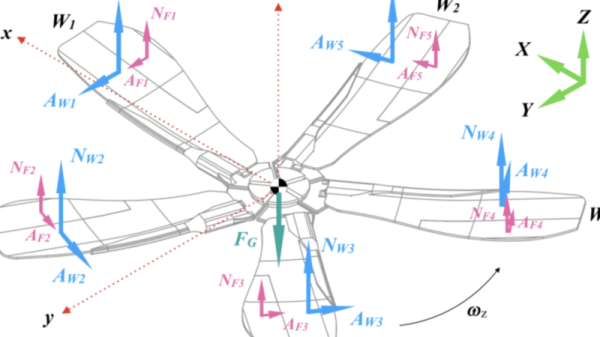

Researchers from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) recently released a video showing their nature-inspired drone that is capable of breaking out into five separate smaller drones. The drones each have auto-rotating wings that slow their rate of descent, similar to seed pods from a maple tree. Due to their design, the drones are only made to be used for a one-way trip, with the five components each carrying a separate payload. The drones are designed to detach within a specified distance from their destination, allow the collective body to safely spiral downwards towards land.

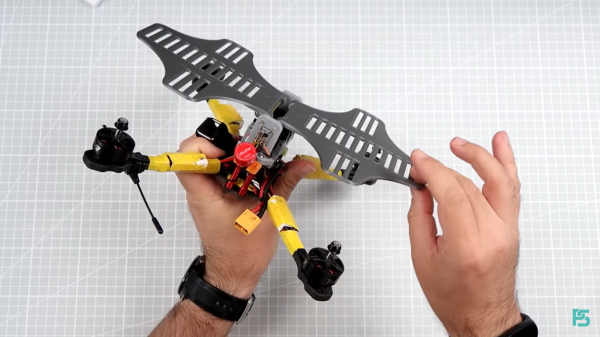

In their paper published on the same subject, the researchers discuss how they optimized the balsa wood wings with servos, a LiPo battery, and a receiver attached to a 3D-printed body. Four are equipped with just these components, while the fifth also holds a 3-axis magnetometer, a Teensy 3.5 board, a GPS module, and a Pixracer controller.

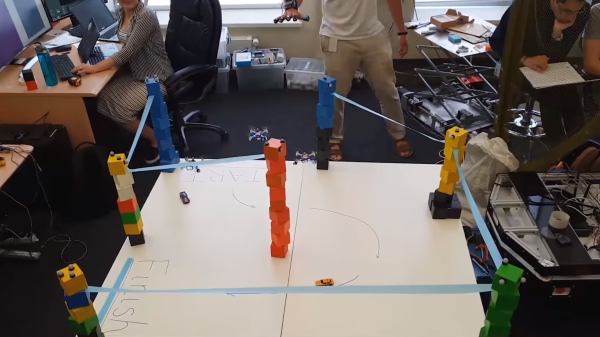

They experimented with several motion capture setups and free-flight drop tests to verify their simulations on the models for the drones. Apart from simply detaching, they are also designed to cater to different mission profiles based on the environment they are dropped in.

We’ll admit that the implementation and design of the drones does seem fairly dystopian, especially when you wonder what could possibly be the payloads these drones are designed to carry. But in terms of nature-inspired robotics, the maple seed pod idea is pretty interesting.

Continue reading “These Maple Pod Inspired Drones Silently Carry Payloads”