In an ideal world we would never lose our belongings, and not spend a single hour fruitlessly searching for some keys, a piece of luggage, a smartphone or one of the two dozen remote controls which are scattered around the average home these days. Since we do not live in this ideal world, we have had to come up with ways to keep track of our belongings, whether inside or outside our homes, which has led to today’s ubiquitous personal tracking devices.

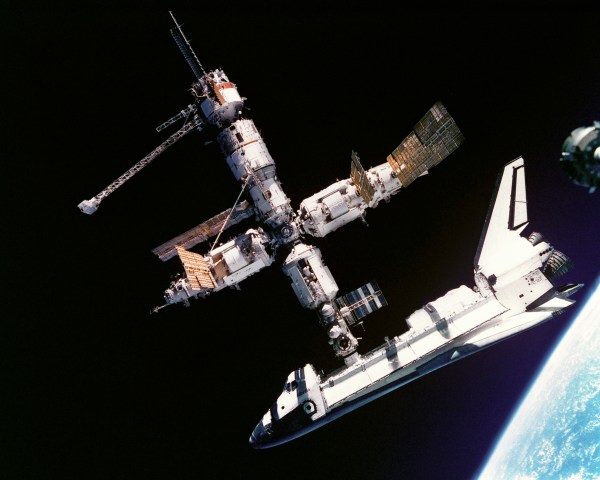

Today’s popular Bluetooth-based trackers constantly announce their presence to devices set up to listen for them. Within a home, this range is generally enough to find the tracker and associated item using a smartphone, after which using special software the tracker can be made to sound its built-in speaker to ease localizing it by ear. Outside the home, these trackers can use mesh networks formed by smartphones and other devices to ‘phone home’ to paired devices.

This is great when it’s your purse. But this also gives anyone the ability to stick such a tracker device onto a victim’s belongings and track them without their consent, for whatever nefarious purpose. Yet it is this duality between useful and illegal that has people on edge when it comes to these trackers. How can we still use the benefits they offer, without giving stalkers and criminals free reign? A draft proposal by Apple and Google, submitted to the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), seeks to address these points but it remains complicated.

Continue reading “AirTags, Tiles, SmartTags And The Dilemmas Of Personal Tracking Devices”