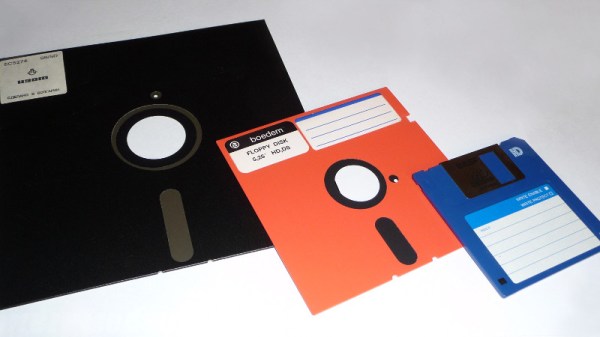

About a week ago, Linus Torvalds made a software commit which has an air about it of the end of an era. The code in question contains a few patches to the driver for native floppy disc controllers. What makes it worthy of note is that he remarks that the floppy driver is now orphaned. Its maintainer no longer has working floppy hardware upon which to test the software, and Linus remarks that “I think the driver can be considered pretty much dead from an actual hardware standpoint“, though he does point out that active support remains for USB floppy drives.

It’s a very reasonable view to have arrived at because outside the realm of retrocomputing the physical rather than virtual floppy disk has all but disappeared. It’s well over a decade since they ceased to be fitted to desktop and laptop computers, and where once they were a staple of any office they now exist only in the “save” icon on your wordprocessor. The floppy is dead, and has been for a long time.

Still, Linus’ quiet announcement comes as a minor jolt to anyone of A Certain Age for whom the floppy disk and the computer were once inseparable. When your digital life resided not in your phone or on the cloud but in a plastic box of floppies, those disks meant something. There was a social impact to the floppy as well as a technological one, they were a physical token that could contain your treasured ephemeral possessions, a modern-day keepsake locket for the digital age. We may have stopped using them over a decade ago, but somehow they are still a part of our computing DNA.

So while for some of you the Retrotechtacular series is about rare and unusual technology from years past, it’s time to take a look at something ubiquitous that we all think we know. Where did the floppy disk come from, where is it still with us, and aside from that save icon what legacies has it bestowed upon us?

Continue reading “Retrotechtacular: The Floppy Disk Orphaned By Linux”