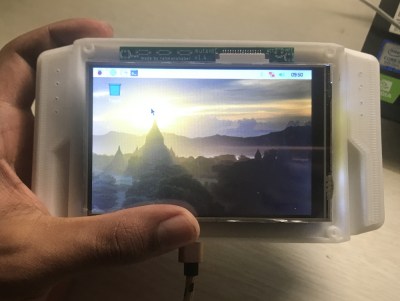

Ostensibly the ESPboy is an open-source hackable game engine built as an IoT platform for STEM education and play, but there’s no way [RomanS] could have been inspired by anything other than retro gaming consoles from the near past. For anyone who grew up playing with Tamagotchi pets or Palm Pilots, this project is going to be a major throwback.

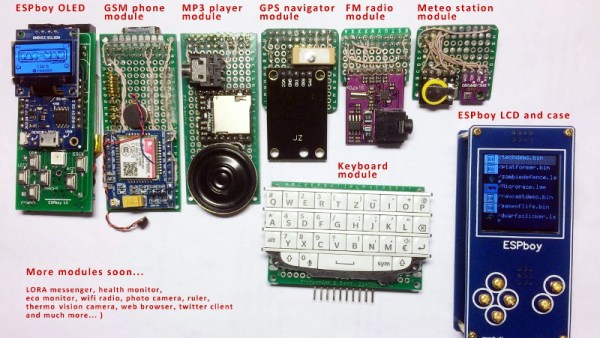

The Saint Petersburg-based microcontroller hobbyist utilizes a ESP8266 microcontroller to build a series of modules for different game play modes, including a TFT display, GSM phone, MP3 player, GPS navigator, FM radio, and keyboard module. He has plans to build even more modules, including a LoRa messenger and thermal camera, to really expand the system’s capabilities.

Since the board has built-in WiFi, firmware can be uploaded to the device without a wired connection and compiler. The nature of the project makes the board compatible with the Arduino IDE and Micropython, which makes hacking the software even easier.

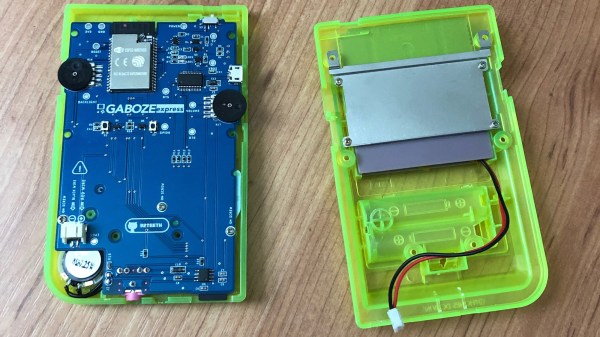

A TP4056 battery charging module charges the LiPo, although depending on the battery capacity, the charging current (set by the R3 resistor on the controller) does require some change. A MCP4725 I2C DAC is used for smooth driving the LCD’s backlight. In order to extend the battery life, the battery controller uses sleep mode to periodically wake up to measure and send data, which allows it to extend its battery life without external power. There’s also transistor driven buzzers that provide a little extra feedback to the user when playing games, complete with a variable resistor to adjust the sound volume.

A number of free pins run along the periphery for connecting to other modules, including pins for GPIO extension, sensor adapters, connectors to addressable LEDs, and an extension slot for actuators. For anyone interested in making their own version of the ESPboy, the PCB schematics are accessible online.

Projects like the Arduboy have shown that a small microcontroller-based game system can be equal parts fun and educational, so we’ve been excited to see more of these types of projects popping up during the course of the 2019 Hackaday Prize.

Continue reading “A Retro Gaming Console For The New Generation”

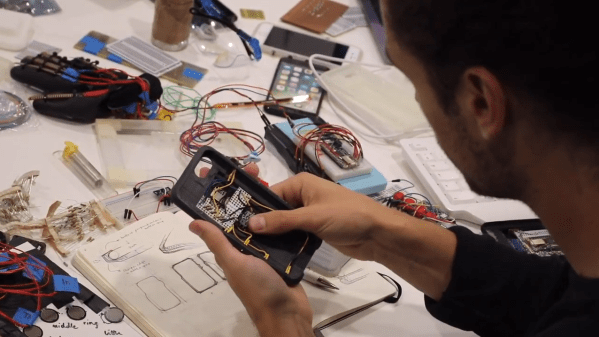

Smartphones and other modern computing devices are wonderful things, but for those with disabilities interacting with them isn’t always easy. In trying to improve accessibility, [Dougie Mann] created

Smartphones and other modern computing devices are wonderful things, but for those with disabilities interacting with them isn’t always easy. In trying to improve accessibility, [Dougie Mann] created

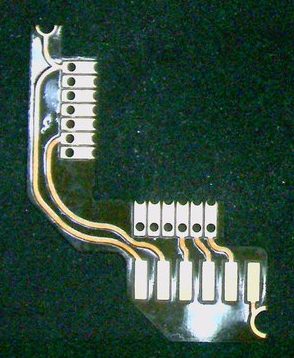

In the mid-90’s Nintendo released the Super Game Boy, a cartridge for the SNES which allowed you to play Game Boy games on the big screen. Each cartridge was in fact an entire Game Boy with the appropriate hardware to present it in a way the host console could interface with, but missing some of the hardware a standalone Game Boy would include like a link port to connect it to another system. This mod fixes this limitation by bridging the correct pins out from the CPU to a breakout board which includes the link port connector. For general background on what’s going on here, check out

In the mid-90’s Nintendo released the Super Game Boy, a cartridge for the SNES which allowed you to play Game Boy games on the big screen. Each cartridge was in fact an entire Game Boy with the appropriate hardware to present it in a way the host console could interface with, but missing some of the hardware a standalone Game Boy would include like a link port to connect it to another system. This mod fixes this limitation by bridging the correct pins out from the CPU to a breakout board which includes the link port connector. For general background on what’s going on here, check out