Badgelife culture is our community’s very own art form, with a plethora of designs coming forth featuring stunning artwork, impressive hardware, and clever software tricks. But sometimes a badge doesn’t need a brace of LEDs or a meme-inspired appearance to be a success, it just needs to be very good at what it does.

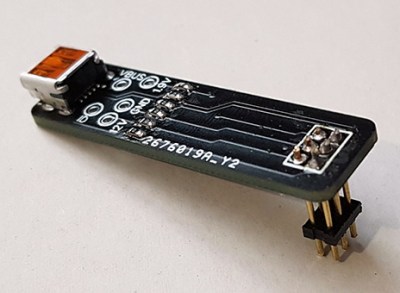

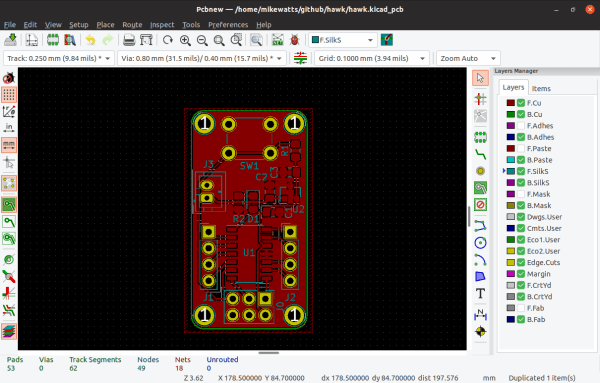

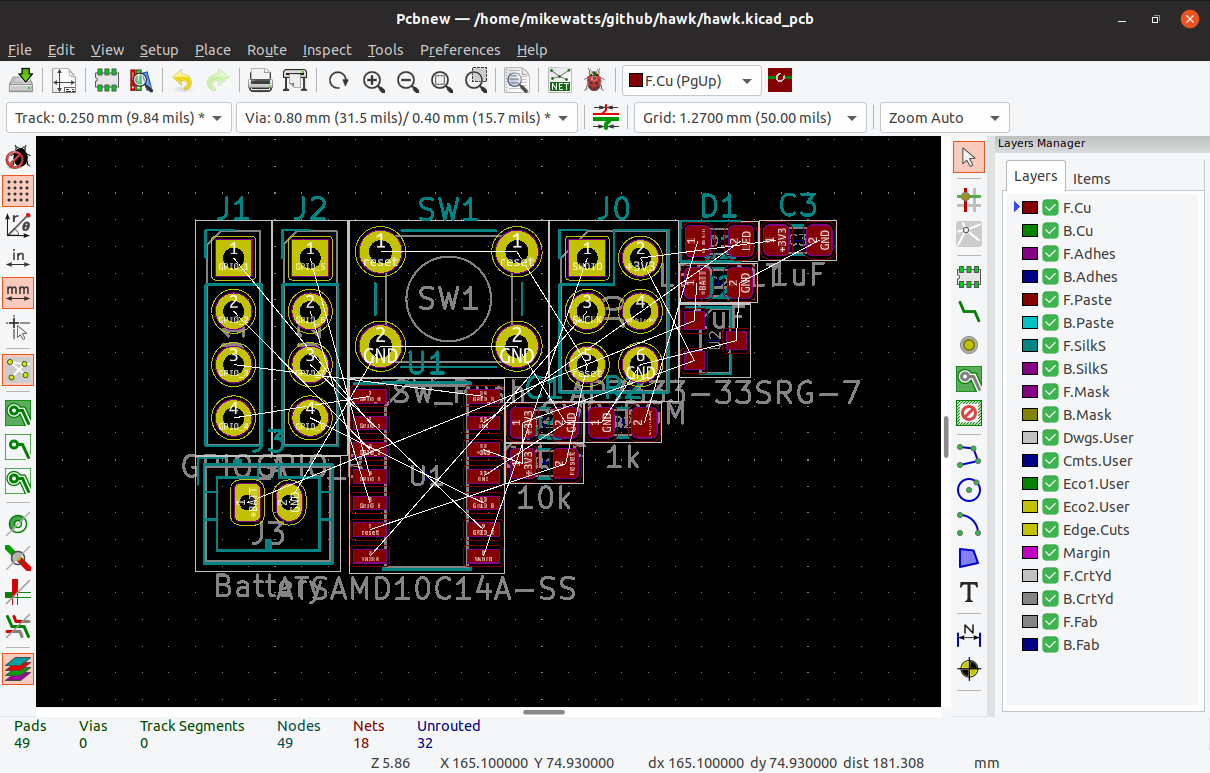

A perfect example is [Gavan Fantom]’s Hello mini badge. The hardware is fairly straightforward, it’s just a small square PCB sporting a LPC1115 microcontroller, 8Mb Flash chip, piezo speaker, and an OLED display. Its functionality is pretty simple as well, in that it exists to display text, images, or short animations. But the badge hides a very well-executed firmware that provides a serial terminal and zmodem file upload capability as well as an on-device interface via a small joystick. Power comes from a 500 mAh lithium-polymer cell, for which the badge integrates the usual charger and power management hardware.

There’s a variety of possibilities for the badge, but we’d guess that most owners will simply use it to display their name with perhaps a little animation. A bit of nifty processing of some video could perhaps get something approaching watchable video on it though, opening up the entertaining possibility of displaying demos or other video content.

[Gavan] will have some of the Hello badges at the upcoming CCCamp hacker camp in Germany if you’re interested, and should be easy enough to find in the EMF village.