At this point, it’s pretty clear that USB-C has become the new standard connector for an increasing amount of applications, but predominantly charging. Even Apple is on board this time, and thanks to backwards compatibility, you don’t have to abandon devices using the older standards you may prefer for their simplicity or superior lint-resilience either. For [Mat] on the other hand, it’s USB-C all the way nowadays. Yet back in the day when he bought his laptop, he had the price tag convince him otherwise, and has come to regret it, as all the convenience of a slim design is cancelled out by dragging a bulky charger for the laptop’s proprietary charging port along.

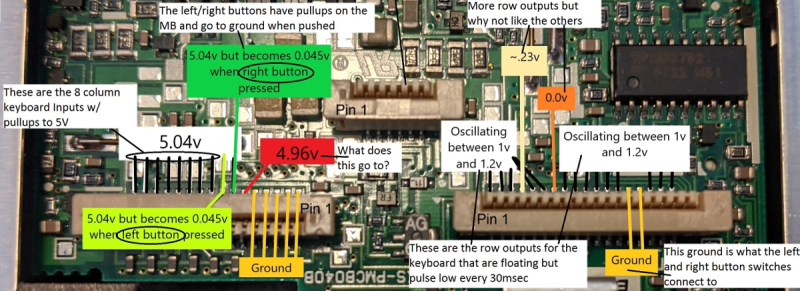

Well, as the saying goes for situations like this: love it, leave it, or get out the tools and rework that sucker. Lucky enough, the original charger provides 20 V, which matches nicely the USB power delivery (PD) specification, and after opening up the laptop, [Mat] was happy to see that the interior provided enough room to fit the USB-C module he was planning to use. Even better, the charging port itself was a standalone component attached to a cable, so no modifications to the mainboard were necessary. Once the USB-C module was soldered to that same cable, the only thing left to do was carving a bigger hole on the laptop case, and saying good bye to the obsoleted charger.

The downside is of course the lack of actual USB functionality with that shiny new charging port, but that was never the goal here anyway. With more and more USB-C devices popping up, it’s also no surprise that we’ve seen modifications like this before, and not only with laptops. In case you’re thinking of upgrading one of your own devices to USB-C, and do wish for actual USB functionality, don’t worry, we got you covered as well.

Continue reading “Solving Buyer’s Remorse With A Rotary Tool And Soldering Iron”