There’s something both satisfying and sad about seeing an aging performer who used to pack a full house now playing at a local bar or casino. That’s kind of how we felt looking at [Craig’s] modern-day bubble memory build. We totally get, however, the desire to finish off that project you thought would be cool four decades ago and [Craig] seems to be well on the way to doing just that.

If you don’t recall, bubble memory was going to totally wipe out the hard drive industry back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A byproduct of research on twistor memory, the technology relied on tiny magnetic domains or bubbles circulating on a thin film. Bits circulated to the edge of the film where they were read using a magnetic pickup. Then a write head put them back at the other edge to continue their journey. It was very much like the old delay line memories, but with tiny magnetic domains instead of pressure waves through mercury.

If you don’t recall, bubble memory was going to totally wipe out the hard drive industry back in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A byproduct of research on twistor memory, the technology relied on tiny magnetic domains or bubbles circulating on a thin film. Bits circulated to the edge of the film where they were read using a magnetic pickup. Then a write head put them back at the other edge to continue their journey. It was very much like the old delay line memories, but with tiny magnetic domains instead of pressure waves through mercury.

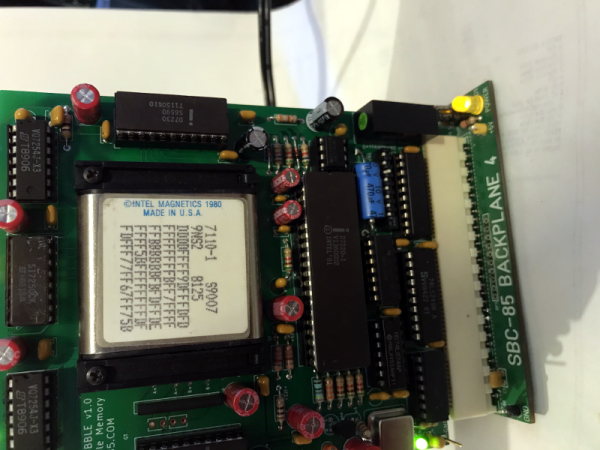

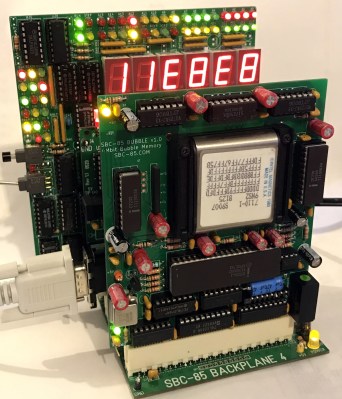

We don’t know where [Craig] got his Intel 7110 but they are very pricey nowadays thanks to their rarity. In some cases, it’s cheaper to buy some equipment that used bubble memory and steal the devices from the board. You can tell that [Craig] was very careful working his way to testing the full board.

Because these were state-of-the-art in their day, the chips have extra loops and would map out the bad loops. Since the bubble memory is nonvolatile, that should be a one time setup at the factory. However, in case you lost the map, the same information appears on the chip’s label. [Craig’s] first test was to read the map and compare it to the chip’s printed label. They matched, so that’s a great sign the chip is in good working order and the circuit is able to read, at least.

We’ve talked about bubble memory before along with many other defunct forms of storage. There were a few military applications that took advantage of the non-mechanical nature of the device and that’s why the Navy’s NEETS program has a section about them.